You’re not likely to notice them at first. Amidst the camouflage, khaki, Hawaiian shirts and olive green tactical vests, a scarf is probably going to be the fifth or sixth thing that catches your eye. But look closely at a group of Boogaloo Bois or Oath Keepers — or any member of far-right militia organizations for that matter — and you’re likely to see a keffiyeh.

When you can't decide if you wanna be a neo nazi or a jihadist so you just bottle bleach your hair and throw on a keffiyeh. #boogaloo #Hamas pic.twitter.com/CKbgmSwEVL

— RandomNYCPerson ? (@RandomNYCPerson) September 4, 2020

The pairing, particularly during the insurrection at the capitol on January 6th, is a bizarre one, to the say the least. It’s especially jarring when you consider that the keffiyeh has pulsed its way through the 20th and 21st century as a symbol of Palestinian liberation. The chequered design modeled after Palestinian fisherman nets first popped up in Mandatory Palestine — a geopolitical entity established under the terms of a League of Nations mandate — in the 1930s. “Men wore all sorts of different things on their head that indicated class,” says Rochelle Davis, director of the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University. “It indicated where they were from — urban areas or the rural areas.”

But once the Great Revolt kicked off in 1936 with a general strike, the revolutionaries encouraged men of all classes to give up other headwear and wear the keffiyeh as a symbol of solidarity. It helped too that draping a scarf over their sun-kissed faces made it more difficult for the British authorities to single out orchestrators of the rural-led uprising.

From that point on, the keffiyeh was no longer merely cotton garb used to block the desert sun; during the Great Revolt it was consecrated as a symbol of liberation, decolonization and national struggle. But it would take another 30 years for the garment, which gets its name from the city of Kufa in Iraq, to make the nearly 6,000-mile journey over the Atlantic and into the U.S. In the 1960s — when the Palestinian armed resistance became more prominent — there were people in the West who wore the keffiyeh in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle for liberation, according to cultural anthropologist Ted Swedenburg.

“Any Palestinian that you knew in like, 1969, 1970, 1971, in the U.S. who was a student in the U.S. would have one,” Swedenburg tells me. But even then, different color keffiyehs meant different things. For example, back then, a red and white Jordanian version began to surface, which was a way for Palestinian Marxists to differentiate themselves within the wider nationalist movement. Similarly, Leila Khaled, a female member of the armed wing of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine also notably wore a keffiyeh in the style of a Muslim woman’s hijab. According to a report in The Guardian, this was highly unusual considering the keffiyeh was associated with Arab masculinity. “Many believe this to be something of a fashion statement by Khaled, denoting her equality with men in the Palestinian armed struggle,” writes Rachel Shabi.

By 1980, the meaning of a keffiyeh in the West had been diluted. The scarf, no longer worn around the head but instead wrapped around the neck of Westerners, began to pop up at anti-nuke and anti-apartheid demonstrations, as well as in solidarity with Central American liberation movements. “That’s also when the keffiyeh started to bleed into what you’d call hipster or subcultural kind of wear,” says Swedenburg, who recalls seeing the scarf being sold by street vendors in major cities around the U.S. “It became a general symbol of dissent.”

In 1987, after the First Intifada began, images of young Palestinians throwing stones at Israeli occupiers armed with M16s and tanks permeated Western consciousness. It was again the keffiyeh that signified empathy for the plight of the Palestinian. “That moment did a great deal to flip people’s consciousness in the West about what was going on and who one might want to be sympathetic with,” says Swedenburg. “[The keffiyeh] was especially common amongst American leftists.”

The trend, however, would largely fade in the late 1990s, only to re-emerge in a post-9/11 world. With the U.S. embroiled in two different wars in the Middle East, for American soldiers serving abroad, the use of a keffiyeh became tactical. Spending hours in the desert, sometimes alongside national Afghani and Iraqi forces, U.S. soldiers recognized the need for something to keep the dust out of their eyes.

It didn’t take long for those images of soldiers to make the journey home. And in 2007, the keffiyeh became part of a major fashion trend among hipsters allured by its activist-chic credentials. “We noticed club kids were wearing them about a year and a half ago,” Melanie Rickey, formerly the fashion news director at Grazia magazine told The Guardian at the time. “They were dyeing them fluorescent colors, and it was seen as a bit risque.”

Per a 2007 story in the New York Times, the scarf was marketed by Urban Outfitters as an “anti-war statement.” Not long afterward, however, the $20 imitations were quickly pulled from shelves, and Urban Outfitters released an apology when a post on the Jewish blog Jewschool complained of its association with terrorist organizations.

Sadly, the post-9/11 style trend also quickly led to a rapid decline in Palestinian-produced keffiyehs, which were already in decline after the 1993 Oslo Accords opened up the region to different trading partners. Wholesalers in the Palestinian Territories, according to a 2011 report from the BBC, increasingly bought cheaper versions of the scarf from China, Jordan and Syria. Back then, the wholesale price of a scarf from Hirbawi Textiles — the last keffiyeh manufacturer in Palestine — cost around $6, while a Chinese version was as little as $3. In fact, Swedenburg tells me that by the time his son, who served in Afghanistan in 2010, was buying a keffiyeh from a supplier on his base, they were “probably coming from China.”

But the cross-cultural pollination, brought on by an ever-globalized world, doesn’t stop there. Davis tells me that one of the things that she’s been tracking as part of her research is how the U.S. military picks up things Iraqis do and vice versa. For example, she tells me that during the U.S. occupation in Iraq, Iraqis suddenly started wearing “wrap-around Oakley sunglasses.” Which, she says, they never wore before 2003.

Cultural transactions like the one Davis suggests are inevitable amongst warring cultures. Swedenburg, though, offers a slightly different theory: “If you put on what the enemy has, you respect the enemy, not necessarily as great humans, but as somebody who’s fearsome and who is a serious opponent. Put on what they’re wearing, and it gives you some kind of magical potency.”

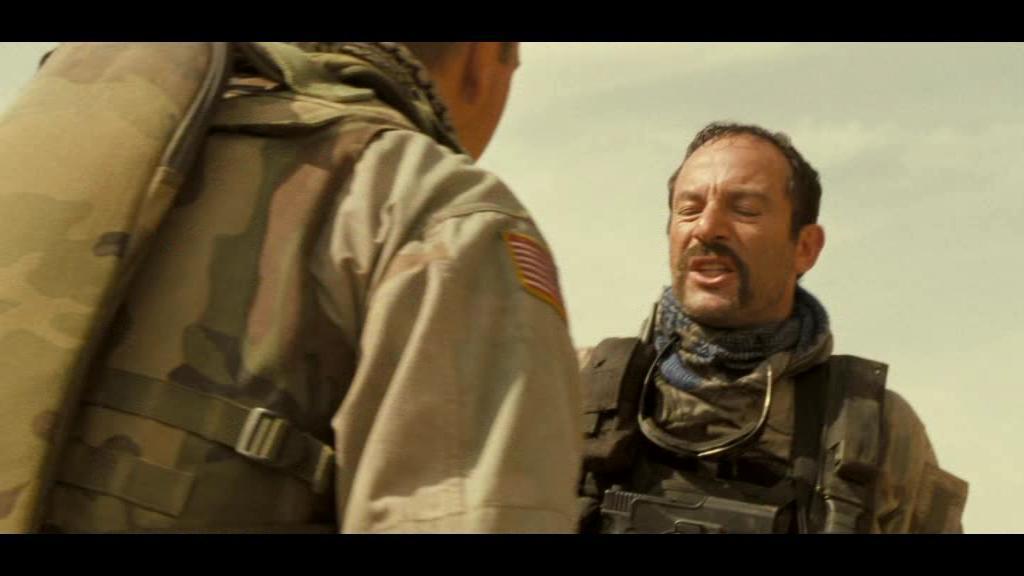

Echoes of Swedenburg’s premise are rife in Hollywood blockbusters. He first noticed the phenomenon in the 1999 film Three Kings, which is about soldiers fighting in the first Gulf War who, after hearing of Saddam Hussein’s hidden gold, set out to find it. “Ice Cube is wearing a keffiyeh the whole time,” he says. The scarf also appears in the 2008 film The Hurt Locker: “Brian Geraghty’s character wears one,” says Swedenburg. “He wears it really neat because he’s the neat, by-the-rules guy and then the out-of-control guy played by Ralph Fiennes wears one wild and over his head.” In the 2010 movie Green Zone there’s a similar motif. Matt Damon wears one, tucked under his uniform’s collar. “While Jason Isaacs’ character, who’s wild and crazy, wears it more openly,” Swedenburg says.

This latest iteration of the keffiyeh, accompanied with military fatigues and brought on by the forever wars in the Middle East, best explains the recent, far-right rekindling. “A lot of these far-right people are veterans,” says Swedenburg. He goes on to cite the work of historian Kathleen Belew and her recent book Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. Belew finds a surprising genesis for the far-right movement in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. Much like the veterans returning home from the Middle East, Vietnam vets also returned home to little celebration and a country besieged by transformation.

“To me, the keffiyeh was 100 percent a symbol of just how many of the people on January 6th were from the military,” says Davis. For those servicemen and women amongst the insurrectionists, the storming of the capitol was by Davis’ same equation the war following them home. “They gear up and they approach U.S. citizens as if they were a military force occupying Iraq,” Davis explains. “They look at citizens the same way.” And the keffiyeh is their marker: “They say to a person, ‘I served in Iraq or Afghanistan. I was a military person. I’m a badass. Don’t mess with me.’”

By that same token, for the insurrectionists who have never served, the keffiyeh is a way to feign credibility. “They’ve become a sort of sign of masculinity,” says Davis. “There are the people who want to cosplay and be like veterans so they go out and buy the MAGA hat and the keffiyeh.”

The irony, of course, is that many of the people among those storming the capitol were, amongst other things, xenophobic. But even then it’s not dissimilar from another phenomenon amongst U.S. soldiers who’ve gotten tattoos that say “kafir” on their bodies. “Kafir means infidel in Arabic,” Davis explains. “They get it tattooed on their body in Arabic, asserting that they are an infidel, but they do it in the very language of the people they are despising in the process of it.”

Setting aside the keffiyeh’s practical purposes — which Davis notes has been obvious to those in the Middle East for centuries — the keffiyeh in its more contemporary iterations is, if nothing else, a symbol of allegiance. To what exactly is murky and often contradictory. But one thing is certain: As it’s pulled further and further away from its birthplace, justifying its purpose appears to matter less and less.