Bruce is a 56-year-old man who’s never eaten a vegetable in his life. His mom claims she fed him pureed peas when he was a baby, but he’s not buying it. “I’ll straight up gag if I try to swallow vegetables,” he says. “Every single time.”

So now the Scranton, Pennsylvania, father of two subsists primarily on chicken. “Lots and lots of chicken,” he explains — typically oven-roasted with a generous side of mashed potatoes, rice or noodles. When Bruce isn’t biting into one of the 8 billion chickens consumed in the U.S. every year (and washing it down with “oodles and oodles of Diet Coke”), he nukes a box of mac ’n’ cheese, preferably Velveeta Shells. Meanwhile, breakfast includes a bagel or “something straightforward” like Cheerios or Rice Chex. Pizza’s good for lunch provided it’s plain cheese or pepperoni. Otherwise, twice a week, he’ll drive thru McDonald’s for a 10-piece Chicken McNugget with fries.

Yes, Bruce is a man who eats like a boy.

Nor is Bruce alone, according to Nancy Zucker, director of the Duke Center for Eating Disorders. As she told the New York Times in 2015, in a sample of 2,600 adults who identified themselves as picky eaters, 75 percent reported that the pattern started in childhood. As it did for Bruce, who says his middle-aged diet is virtually indistinguishable from the one he kept throughout adolescence.

“Most of what I make for dinner are things my mother made,” he explains, as is his usual restaurant order of spaghetti and meatballs. Thankfully, he says he’s less OCD about it now. Vegetables hidden in spaghetti sauce used to freak him out — he feared they’d infect the entire plate — but now, he explains, “I just kinda nudge them aside and work my way around the meal.” He does admit, though, that it’s “peculiar to be 56 years old with all that stuff piling up along the edge of your plate.”

Some people naturally grow out of this type of eating, explains David Wiss, MEL’s go-to dietitian from Nutrition in Recovery in L.A. “But a lot of people are trapped in a 10-year-old version of themselves and never reach nutritional adulthood.” Wiss adds that he thinks the phenomenon is more pronounced in men. “It’s become more culturally acceptable for a man to reject fruits and veggies,” he explains, “whereas traditionally, females have been the family caretakers and more likely to engage in specific nutrition behavior.”

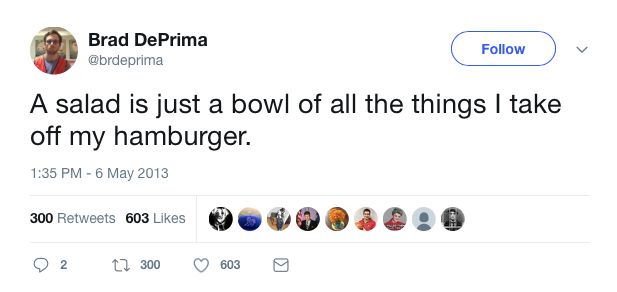

The proclivity to eat like a boy is only magnified when there’s a partner around to bear witness. For example, when Ally met her boyfriend Brad, he didn’t eat vegetables at all, only steak, pasta, burgers, nuggets and pizza bagels. “He’s 28 now, and he still eats like a 7-year-old,” Ally tells me. “He works at Family Guy, so he’s surrounded by other adult children and a kitchen fully stocked with gummy bears and Capri Sun. What adult man regularly drinks chocolate milk with his meals?”

Ally chalks it up to Brad’s mom babying him and bowing to his every dietary whim when he was a child. “She’d cook three different meals if he and his brothers demanded it,” she explains. “So Brad was an incredibly picky eater after 20-some-odd years of being nutritionally catered to by his (very lovely) mother.”

“Yes, I was a super picky eater when I was little,” Brad admits over email. “My three main food groups were pastas (+ mac ’n’ cheese), hot dogs and chicken nuggets. I’d also have a milkshake before bed.”

“Seriously, dude?” Ally asked after watching Brad eat buttered noodles off a paper plate for the fourth night in a row. She’s slowly expanded his culinary horizons since then, helping him realize the foods he “didn’t like” were based on opinions he’d formed as a 7-year-old. “Just try it,” became her mantra, and more often than not, he’d actually like it — to his own surprise. Two nights ago Brad even made pasta from scratch and washed it down with a glass of organic chocolate soy milk, and he now buys organic pizza bagels from Whole Foods.

He still, however, maintains elements of the childish diet. “If he orders Chinese, he’ll meticulously pick every vegetable out of the chicken lo mein,” says Ally. “I like vegetables, so I’ll eat whatever he discards. At this point, I find it endearing.”

Sometimes, though, it’s less about being picky and more about survival. “My mom couldn’t cook to save her life,” says Evan, a 22-year-old from New Jersey. “Our typical dinner ranged from meatloaf (which was terrible) to mac ’n’ cheese (which was also terrible).” Soon, Evan began skipping dinners and eating hot dogs and cereal on his own — a menu he’s maintained into adulthood. “I pack lunch five days a week to save money,” he explains. “And by ‘pack,’ I mean roll up hot dogs and white bread into tinfoil and stuff them into my laptop bag.”

As for Bruce’s mom, he says she pressured him to eat more fruits and vegetables — there were, in fact, many long nights sitting at the dinner table staring at a bowl of peas. (He claims he always outlasted her.) “One day you’re going to meet a pretty girl and she’s gonna smile and serve you peas,” his mom would tease. “Then you’ll eat them.” That’s yet to happen, Bruce explains, despite being married to the same woman for 21 years.

Picky eating starts early, explains Wiss, who says highly-processed foods — e.g., Lunchables, Goldfish, Twinkies, Fruit Loops, Pop-Tarts and Go-Gurt — make it clear to a child’s growing brain which food is the most dopaminergic(i.e., rewarding). As the child ages, Wiss says they’ll eat even fewer nutritious things, like vegetables, that mom used to make them eat, thus becoming even more intolerant of “healthy” food.

In severe cases, if the child attempts to eat unprocessed whole foods like lentils, their body won’t be able to break them down (because, you know, they’ve never had to before). “Whole foods require a lot of work and release less dopamine in the brain,” Wiss says. “So why would someone consume them?” (The reason they should, he explains, is because a “child’s diet” low in phytochemicals and fiber can lead to chronic disease including cancer, hypertension, diabetes and obesity.)

“We have an overwhelming cultural message in America that healthy food doesn’t taste good and junk food does,” agrees Dina Rose, a sociologist, feeding expert and author of It’s Not About the Broccoli: Three Habits to Teach Your Kids for a Lifetime of Healthy Eating. Adding to the misinformation, she tells me, is when parents broker deals with kids by saying things like, “You have to eat two more bites of vegetables if you want to get your dessert,” since rewards imply they’re doing something difficult and unpleasant.

That’s exactly the type of nagging mother Hannah, a 23-year-old in Pittsburgh, doesn’t want to be with her boyfriend. On their first date at a bar, she tells me, he ordered lettuce, pickles and onions on his burger — just to impress her. Despite his primary food group being bagels (he admits to eating more than 300 a year), Hannah reminds herself that he’s not actually a 12-year-old boy — despite eating like one — and she’s not actually his mother, pestering him to finish his greens.

She admits her boyfriend’s poor nutrition occasionally causes minor conflicts, like when the only meal he’s able to offer her is a burger on the George Foreman Grill. She’s not annoyed by it so much as unnerved by a perceived gender imbalance. “Women are taught to cook at a younger age,” she notes. “Sometimes I worry I’ve fallen into a traditional ‘Woman in the Kitchen’ gender role, but then I remember I like cooking and it’s easy to cook for someone who’s impressed when I put cheese in scrambled eggs.” Besides, she adds, he’s actually started buying and cooking himself eggs. “But 80–90 percent of his diet would still appeal to a child.”

Perhaps male distaste for vegetables stems from their limited experience with dieting. At least that’s the hypothesis of Stephanie from New York, who says all of the men in her life — dad, brother-in-law, men she’s dated — eat like boys to varying degrees. “The biggest thing I notice is how much more carefree they are about food,” she says. It makes her envious, she admits, as she says it would for anyone who’s hyper-conscious of calories. “While I know men have plenty of body image issues, too, in general I find them blissfully free of the mental gymnastics one can go through when deciding what to eat. It seems great.”

Incidentally, none of the men I spoke with even had wrestled with the idea that their eating might be disordered. (Mike says he does have an anxiety disorder, which likely factors into his picky eating.) “I’ve never considered my eating preferences to be a disorder,” Bruce says, more or less speaking for the group. “I’m much pickier than others, but I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.”

That doesn’t mean, however, that they’re unaware of the consequences of what they’re putting in their mouths three times a day. “I’m sure I’ll pay for it down the road, but I’ve always been athletic so I never really gain weight eating trash,” says Christopher, a 22-year-old “humble black man” from Chicago’s southwest suburbs. “I honestly eat the same stuff now that I did when I was a kid: Either Portillo’s Hot Dogs or any other fast-food restaurant.”

“I have plenty of opportunities to change my diet,” he continues. “I just want to forgo the big change. Women tell me I eat like a 9-year-old all the time. It’s not really offensive though, it’s just one of those things. If anything, we need more people like me. Sushi is trash even though it looks cool. Instead, I’m lowkey trying to get a taste of every burger in Illinois. Yung burger enthusiast.”

Bruce says he’s already bigger than he ought to be, which is why he limits the 10-piece McNugget run to twice a week. “For lunch the other days, I’ll have a hoagie with ham and Swiss or turkey and nothing else — no spices, no mayo, no veggies — just meat, bread and cheese.” The taste of healthy sandwich garnishes doesn’t bother Bruce that much; it’s more their consistency, he says. “I just don’t like the way that stuff feels in my mouth.”

Wiss explains that this is because a predominantly “meat-and-potatoes diet” — i.e., low on fiber and plant foods, high on animal products — causes the body to reject natural things that nourish us. “It’s an incredibly bizarre phenomenon and goes against the principles of survival to reject the things that will prevent chronic disease,” Wiss explains, “but a signaling cascade from the gut to the brain is mediated through texture. The tongue is able to detect right away if something is highly palatable (like quesadillas) or fibrous and foreign (like Brussels sprouts). That’s why picky eaters usually blame the texture of the food.”

Wiss notes that the realities of selective eating disorder can be complicated since it has to do with the neurobiology of preference. “With respect to food, reward pathways are paved so early that some people never dare to venture out,” he explains. Further complicating things is when the relationship with food is developed alongside trauma. “Most food aversions can be overcome,” he explains, “but there are some that might not. A lot of people have food trauma linked to early childhood — for example, being a 5-year-old and having your parents fight in the background while they make you eat canned green beans.”

Somewhat similarly, he says many people associate being force-fed food they don’t want with a lack of independence. “That’s a very masculine trait: You can’t tell me what to eat. I eat what I want to eat!” Or as Mike, a 30-year-old working class man from Pittsburgh, puts it: “Adults were always trying to get me to eat things that I didn’t want to eat and would be legitimately pissed when I didn’t, like it was some insult to them. I like what I like and stick to it. I just don’t really care.”

Leslie from Brooklyn says all of her boyfriend’s meals are kid-friendly. “His usual restaurant order is ginger ale — no ice; room temperature if possible — and fries. Sometimes, two orders of fries. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him order a real entree in a restaurant — not even a hamburger.”

But recently, she’s seen him paying more attention to the physical toll of this Peter Pan diet. “Like most 40-year-old men,” she says, “he’s starting to notice how food affects his body.” So it’s vanity — rather than an abstract idea of health or nutrition — that’s driving him to change his ways.

In fairness, though, it’s also about making Leslie happy. Once, he sent her a selfie from the bathtub eating spinach out of a bag, one leaf at a time. Why was he eating it this way? “He didn’t know how else you were ‘supposed’ to eat them.”

Baby steps.