On September 27, 2001, the satirical newspaper The Onion published a new issue following a brief hiatus due to the September 11th terrorist attacks. It was a precarious time in comedy, with many humorists having yet to return and guys like Letterman and Jon Stewart deciding to play it straight instead of crack a joke. But in their first issue back, The Onion did what it always did — it told jokes. With headlines like “Life Turns Into Bad Jerry Bruckheimer Movie” and “Not Knowing What Else to Do, Woman Bakes American-Flag Cake,” The Onion found the pitch-perfect way to approach humor in a very sensitive time. Now, nearly 20 years later, the issue is widely considered to be an important part of comedy history — even an important part of the broader cultural history surrounding 9/11.

While The Onion’s headquarters back in 2001 may have been in downtown Manhattan, to get the proper context for their landmark issue, the story doesn’t begin in New York. Instead, it begins in Madison, Wisconsin, where The Onion operated from 1988 until just a few months before the 9/11 attacks.

Founded in the late 1980s by University of Wisconsin students Tim Keck and Christopher Johnson, The Onion was born as a weekly humor print publication at their college campus. A year after its debut, Keck and Johnson sold the paper to humorist Scott Dikkers and publisher Peter Haise, who, over time, oversaw The Onion’s transformation into a more satirical form of comedy.

Robert Siegel, The Onion writer, 1994 to 2003; Editor in Chief, 1996 to 2003: The joke was always that The Onion was a bunch of Midwest slackers. It was very different from The National Lampoon, where there were all these ambitious East Coast people fighting to be the top guy. It wasn’t competitive like that. The profile of the typical Onion writer was that they were marginally employed and maybe they had completed their education at the University of Wisconsin. I guess I had a small modicum of ambition and that was enough to differentiate me to become the editor. Plus, no one else really wanted to be the editor.

It was more wacky and silly than it was satirical back then, more of a parody of The Weekly World News. The bite that it eventually had wasn’t really there in the beginning. I’m not trying to take credit for it, but during my time there, I saw it take on a more political point-of-view. The Onion didn’t start with any sort of agenda. It wasn’t started by people that were trying to say anything. It was really just started as something to put around all the pizza coupons. The people who started it wanted to have a newspaper and they knew they wanted to sell local advertising, and they just needed something to put around the local advertising and this silly, fake news format emerged.

Todd Hanson, The Onion head writer, 1990 to 2017: I joined The Onion in the fall of 1990, but I worked there for seven years without it really being my job. It wasn’t until 1997 that we got to quit our day jobs. Before that, it was like being in a garage band. It was something that you did for fun with your friends and nobody had a full-time job there except for the editor in chief, the publisher and the assistant editor.

It wasn’t like we were doing this because we were looking to have a career in comedy or anything like that. I mean, none of us had a comedy background, and none of us had a journalism background. It was just a creative, fun thing to do. A lot of us had been cartoonists for the campus papers. It was like being in a rock ‘n’ roll band that you don’t plan on ever paying the rent with.

From 1990 to 1997, I had working-class jobs like the rest of the staff did. I worked retail, I washed a lot of dishes — a lot of minimum-wage jobs. In 1997 The Onion was doing well enough that they hired us full-time, and that began what I think of as sort of the glory days of The Onion. It was wonderful because you didn’t have to work 40 hours a week making minimum wage in order to pay your rent, you could just do The Onion, so it was a pretty great moment in our lives.

Maria Schneider, The Onion writer, 1991 to 2008; freelance contributor 2009 to present: I joined in 1991 or 1992 and I started as a part-time contributor. They were in this cheapy little office on State Street in Madison. It was very small back then, with only a couple of people on the full-time staff. Early on, The Onion was more of a supermarket tabloid format like the Weekly World News, and we switched to more of a hard news format around 1995 or 1996. I joined the staff full-time around 1997, when The Onion had gotten some national attention and was contracted for our first book, Our Dumb Century.

Mike Loew, graphics editor/writer for The Onion, 1993 to 2007: I started writing for The Onion in 1993, and I knew several of these guys as early as 1991, because I grew up in Appleton, Wisconsin and then went to college in Madison. We had two great student newspapers going daily and I joined up at The Daily Cardinal and met several people who would move over to The Onion. That’s where a lot of The Onion people got their start — they were cartoonists and some of the funniest people at The Daily Cardinal.

In 1996, the paper went from looking like The Weekly World News to USA Today, which was [owner, editor-in-chief] Scott Dikkers’ idea. That’s when the paper went to full color, and I was asked to become the graphics editor. Back then, the paper came in two sections — you had The Onion and then you had the A.V. Club inside, which was its own section.

Chad Nackers, The Onion graphics editor/writer 1997 to 2017; Editor in Chief, 2017 to current: At this time and a few years after the 9/11 issue, the website still felt secondary to us. The print issue felt like it was real because you could hold it in your hands, which was generally the case for most publications back then.

In early 2001, the entire writing staff of The Onion relocated to New York City from Madison. Their office was on 20th Street in Manhattan, but most found apartments in Park Slope, Brooklyn, which one Onion writer even took to calling “Little Wisconsin.”

Hanson: I arrived in New York on January 3, 2001. When we moved to New York, every single staffer was from Madison. It was the relocation of an entire staff. I didn’t even think of us as a staff because we weren’t staffed the way a staff is staffed, with interviews and all that. It was a group of friends. Like, you don’t, apply to be a member of The Ramones, you know what I mean?

Siegel: As for why The Onion moved to New York, well, I think we all just kind of got bored of eating at the same three restaurants in Madison. Madison’s great, I love college towns and I love Madison, but there was a certain point where, at least speaking for myself, I started to feel old there. I was closing in on 30, I’d been there six years. Everyone else had been there longer than that. We all just collectively were ready for a big city adventure. It kind of felt like Muppets Take Manhattan.

Almost as soon as we landed on the shores of Manhattan, we were profiled by The New York Times. We joined the media softball league, and we were suddenly playing softball against The New Yorker and High Times and meeting people and getting invited out places. It was pretty awesome. For a moment there, we were the exciting newcomers and everyone wanted to meet us, but then we never quite took advantage of that. We all just receded into our own space. We kind of replicated our Madison lives in New York.

Loew: All of us moved into the same spot in Park Slope, Brooklyn. John Krewson even came up with calling the neighborhood “Little Wisconsin.”

Carol Kolb, The Onion writer, 1997 to 2005; Editor in Chief, 2003 to 2005; head writer for The Onion News Network, 2006 to 2012: Moving to New York was great. A lot of us had worked at The Onion for a long time and we loved The Onion and we loved that it was getting some national recognition, but we were living in our college town and we didn’t want to live in the same place forever — we wanted to expand our horizons a little, which led to us convincing the business staff that there would be better business opportunities for The Onion in New York. But really, we all just wanted to move to New York, and it worked out.

New York was great for us, and then, suddenly, it was a horrific hellhole.

At 8:46 a.m. on September 11, 2001, American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center. At 9:02 a.m., a second plane hit the South Tower and America realized that it was under attack.

John Krewson, The Onion writer, 1991 to 2012: On the morning of September 11th, everyone was really hungover because the night before we’d had our New York launch party and They Might Be Giants played. It was sponsored by Johnny Walker and Mercedes-Benz — it was at the Bowery Ballroom and we’d stayed up all night and had a great time and drank a ton. We didn’t know it then, of course, but it was the end of the 1990s. It was our last party of the 1990s, and the 2000s were about to really fucking begin.

That morning, I turned on the TV and they had Monday Night Football wrap-ups on CNN. Then I saw the chyron at the bottom of the screen, and it said that a plane hit the World Trade Center. I figured it was probably one of the little postcard planes that takes pictures of lower Manhattan, but then I craned my neck to see the World Trade Center out my window, which were the only buildings in Manhattan that I could see from my window. I looked at the Twin Towers and one of them had a huge hole in it and was smoking. I thought, “Wow, that’s not a small plane. What the hell is happening?”

I ran up the fire escape to my roof just in time to see the second plane hit through my binoculars.

Schneider: That morning I woke up really headache-y from the night before and figured that I’d be late. It was a beautiful morning; I know everyone says that, but it really was. I must have been in the shower, and when I got out, I’d gotten a phone message from my sister, who said to turn on the TV because something had happened, and that I may not want to go into Manhattan today. So I turned on The Today Show and the first tower had just fallen.

Chris Karwowski, The Onion writer 1997 to 2012: A bunch of us went to John’s house later on and congregated on his roof. I just remember that the smoke was blowing into Brooklyn at that point, with charred pieces of paper floating down and you could just grab paper from the buildings.

Loew: Chad and I went into work on September 12th, and no one else was there. I’ll just say, us graphics guys, we don’t get to work from home. All of our files were at the office; we had our big computers that were capable of crunching Photoshop in those years. The writers could type at home and write at home and email stuff in, but we just couldn’t do that with graphics.

So we were the only two people in the office, and there was a black rainbow of smoke still hanging over Chelsea. We were just about a little less than two miles north of ground zero. We looked down 10th Avenue, and for miles and miles down that long, straight avenue you could see it was all emergency vehicles. And that smell, maybe you’ve heard accounts of the smell, but it really was like nothing you’d ever experienced before — like burned hair, heavy metal and fuel. And all the powderized concrete, of course. The stench of death was in the air.

So, Chad and I went in, thinking that we were going to start work on a brand new issue because this was a Wednesday and the front page is due on Friday, so we’ve got two days to bang this out. Rob got in touch with us somehow, I don’t remember how, and told us we have to take the week off, so we were in the office for a couple hours and then went back to Brooklyn and stayed home for the rest of the week.

Krewson: Rob Siegel wanted us to take the day and then do an issue the next week, but the issue that we had planned to put out the next day, that Wednesday, never saw print, we just canceled the whole thing. For one thing, distribution would have been a nightmare. Second of all, we just didn’t think anyone was ready for a bunch of wacky jokes that were no longer relevant.

Tim Harrod, The Onion writer 1997 to 2003: It was Todd who called me the morning of — after he had spoken to Rob — and he passed on the news that we’re going to take a week off and then start fresh. So it was the following Monday that we reconvened in the office.

While The Onion staff took the week off, the conversation about how to proceed with the issue began almost right after the attacks, with several staff members discussing just how they’d return.

Hanson: Right away, I was on the phone with Rob Siegel discussing, “What should we do?” And I remember on the phone arriving at the conclusion that, “Well, whatever we do, we’re not going to do anything that has to do with the Towers.” Because that would be inappropriate because everyone’s traumatized as fuck. Our normal, irreverent, edgy, cynical, dark humor wasn’t going to be emotionally appropriate with this situation.

That only lasted for a very short time, though. Then I remember there was a phase where we decided we were going to do one definitive story that would address the World Trade Center, and then the rest would be lighthearted stuff that would take people’s minds off their troubles. Then we immediately realized that that wasn’t going to work because there wasn’t anything else relevant. And so, we had decided that we’re doing the entire issue about one topic, which wasn’t something that we ever did back then — or maybe we only did once or twice before.

Karwowski: It felt disrespectful to not take it on. If we were just writing normal jokes, avoiding the whole thing, it would have felt like, “What are you guys doing?”

Kolb: I was assistant editor at the time, just under Rob, and the intention wasn’t to do an entire issue about it at first, but everything else felt so inconsequential, so we decided to have the entire issue focus on it.

The Onion officially returned to work in downtown Manhattan on September 17, 2001. Having decided the entire issue would be entirely about 9/11, the question now was, how to do it?

Siegel: By that time we were already under pressure to come back, to, once again, sell pizza coupons more than anything else. It really wasn’t bravery. It was just our owner kind of putting the screws to us and saying, “We’ve got to put out a paper because we can’t really afford not to.” So we got the order from on high saying, “Would you mind putting out a paper this week? It would be really great because we have to pay everyone’s salaries and cover the rent and we can’t really afford another week of no ad revenue.” That was really what it was.

This came from Peter Haise [the owner and publisher] and maybe that’s not exactly how it went, but that’s how I remember it. I mean, if we had given pushback, he probably would have been cool about it, but we didn’t give pushback. The ads were the lifeblood of the thing, so we needed to get back to it to keep our lights on.

Loew: Here’s an interesting point: The Onion hadn’t started print circulation in New York City yet. We’d put out regular issues for subscriptions and for distribution back in Madison and a few other places, but we hadn’t yet begun New York City circulation. This was scheduled to be our first issue available all around New York.

Hanson: It was still a print issue in the cities where it was distributed, but New York wasn’t one of them yet. We had a national and global following by that point on the internet, but most of the people who read it probably didn’t read it in paper. Some people subscribed and we mailed them paper copies, but unless you lived in Madison or one of the other cities where paper was distributed, then you wouldn’t have access to the paper copies without a subscription.

Loew: At some point we realized, “Oh my God, this is going to be the first print paper we’re going to drop on the streets of New York City!” So we had to make it about 9/11, because if we made it about Cheetos or some silly stuff, that would be offensive. But this was terrifying because we’re these kids from Wisconsin coming into New York City and we’re going to drop this silly comedy paper about this horrific tragedy. So we knew we had to get it right — it was like threading the eye of the needle.

Harrod: We’d had almost a week to think about everything when we regathered on Monday. You could say there was the general feeling of, “Can we do this?” hanging over us as we filed in, but once we got started, we found the path through the woods.

I remember throwing out the first idea. Before I get to that though, I have to rewind a little back to Madison in 1999. When Columbine happened, Newsweek had a banner headline of the word, “WHY?” over a picture of grieving people and Todd had suggested back then that the next time there’s a huge tragedy, we should just publish the word “WHY?” over a picture of a chicken crossing a road. I reminded everyone of that — I wasn’t seriously suggesting the idea, but that helped to break the ice a bit.

Hanson: We were very terrified about people being offended, which is very, very, very interesting and different about this issue because normally when a new issue came out, we had absolutely no concerns about whether we were going to offend people. In fact, if people were offended, we enjoyed that. If anything, we were proud when we offended people. But this time we weren’t feeling that way. That was an exception to the norm. Everything about this issue was really an exception to the norm, to be honest.

Krewson: No one was sure what to do, and everyone was still in shock. We didn’t want to be jingoistic. It didn’t take too long — less than 24 hours — for people to say, “Oh, well, we’re going to war in Iraq.” And, I don’t know if anybody here is up on the spoilers, but we did that and, to this day, I’m not really fucking sure exactly why that was the case. We also didn’t want to do, “It’s the U.S.’s chickens coming home to roost.” That’s a bullshit line of thinking because if you say “we had it coming,” then you’re saying those people in the buildings had it coming.

It has to be stressed that we weren’t sure we could do it. I remember Joe Garden and I especially were like, “I don’t think we should do this. I don’t know if we should. I think we should maybe take another week and then start back in with a regular one.” But other people on staff were very adamant that we had to do a response to September 11th. I wasn’t sure that was the right thing to do, but I’m really, really happy I was wrong because I’m proud of that issue. That issue ended up being a necessary piece of art made by some incredible people who really met the moment really well and I’m glad to have had a small part of it.

Kolb: Our headlines meetings were on Monday and our process was to write a bunch of headlines on the weekend — usually late Sunday at the last minute — and then to come in on Monday for our headline meeting, and it was a regular work week in that regard.

Loew: We all got back in and we all sat together, pitching headlines, trying to find the right tone. We’ve got to cover it from this angle, we’ve got to cover it from that angle. What about the average person at home, how are they handling it? That’s where “Woman Bakes American-Flag Cake” comes from. We have to capture some of this righteous anger, so “Hijackers Surprised to Find Selves in Hell.” The one that always tickled me was “Rest of Country Temporarily Feels Deep Affection for New York.”

Schneider: I don’t know if this was articulated, but we didn’t want to rattle people’s cages too much or do any sort of “too soon” type humor. I don’t think Rob Siegel got up and said, “We don’t want to do this!” but I think in the aftermath of a shocking incident, you’re in the mood for some things and not in the mood for other things.

Hanson: I remember one headline in particular that was really great as an Onion headline. It was really perfect and it was the sort of joke we would normally make, but we were like, “This isn’t a normal issue, and so, we just can’t do it.” The headline was “America Stronger Than Ever Says Quadragon Officials.” Of course, the idea being that one whole section of the Pentagon was missing. It was great for an Onion joke, but people died, so we just couldn’t do that. Not in this issue.

Krewson: I don’t think anyone actually said this in as many words, but we just started taking all our moods and designing stories around them. Because you can’t ever say the terrible thing is funny, but you can get some mileage out of making fun of the people who did the terrible thing, or studying people’s reactions to the terrible thing.

“American Life Turns Into Bad Jerry Bruckheimer Movie” was the first story that I think we all agreed on. That was either a Joe Garden or a Todd Hanson headline, and once we realized that there was a way to do an issue about this, the pressure came off a lot. Then suddenly the floodgates opened, but it was still the hardest issue we’d ever put together.

Siegel: Everything in that issue either needed to make a point or express something people were feeling.

Loew: We wouldn’t have done it if we were just alone, I don’t think. The fact that we could pool all of our intellect and all of our creativity and energy into something like The Onion — that’s how we did it. Also, there’s no bylines in The Onion. There’s no “story by Todd Hanson” or “photo by Mike Loew,” it’s all just all by The Onion. I think that also gave us some freedom and a sense of safety in that we’re not putting ourselves on the line. At least we’re all together.

Deciding what went into the issue took place over several meetings, and we went over everything with a fine-tooth comb that week. It was still a standard schedule though. Like usual, the writers were supposed to show up with X amount of headlines for the idea meeting. So the writers came in with their lists, they read their list, and from that, they created a master list with hundreds of ideas and then you picked an issue from that master list.

Krewson: It came slowly, but we were so in the habit of making these issues that getting back to our routine gave a sense of normalcy to what we were doing.

Siegel: Most of the time, it’s just obvious who should write what, given their voice and their beat. While generally whoever pitches a headline doesn’t necessarily write the story, with this issue people more so wrote what they pitched.

Nackers: You had a great group of people who knew each other really well and knew their beat, so you had great, well-rounded coverage for the issue. Also, because we were New Yorkers who recently moved from the Midwest, we were able to sum up both how New Yorkers were feeling and how much of the country was feeling at the time.

The Onion’s 9/11 issue wasn’t the funniest issue they ever did, but it would turn out to be incredibly successful because it reflected so many of the emotions that people were feeling after the attacks. The sorrow, the anger, the utter helplessness — all of this was captured by one headline or another, giving most everyone in the audience something to identify with. A few of those headlines…

“HOLY FUCKING SHIT: Attack on America”

Loew: I’m pretty sure that that might’ve been the spiciest language that we’d ever put on the front page up to that point. We were trying to capture just the general shock of the moment. I’m not sure who, but someone said, how about we just say, “Holy Fucking Shit.” That might have been Rob Siegel — I think it was Rob Siegel.

Siegel: It’s kind of become known as the “Holy Fucking Shit” issue because there’s a little “Holy Fucking Shit” logo on it, which I can claim credit for. A lot of the time, you can’t remember what you wrote and what someone else wrote, but that, I will say, I did. That was because, at the time, every network had these dramatic logos with the twin towers burning saying “Crisis” or “Terror in America,” or whatever; so we just said, “Holy Fucking Shit” because that’s what most people were actually thinking.

“U.S. Vows to Defeat Whoever It Is We’re at War With”

“[President Bush:] ‘The United States is preparing to strike, directly and decisively, against you, whoever you are, just as soon as we have a rough idea of your identity and a reasonably decent estimate as to where your base is located.’”

Harrod: I believe I took a stab at “U.S. Vows to Defeat Whoever It Is We’re at War With,” which was about the changing face of war. We didn’t, at that moment, actually know where our enemy was, which is normally pretty crucial before you can attack them.

Loew: Even then, we could see where this was heading and that this was going to be used to justify all sorts of military adventures in impoverished countries with people of color.

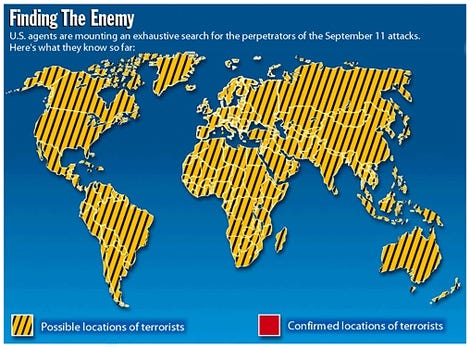

Hanson: My favorite joke in the entire issue was from the story “U.S. Vows to Defeat Whoever It Is We’re at War With,” and it was the graphic showing the world map with possible locations of terrorists. It was so brilliant. I assume the joke was actually made by all of us collaborating together, but it was fabricated by the graphics team of Chad Nackers and Mike Loew. It’s a great visual gag.

“American Life Turns Into Bad Jerry Bruckheimer Movie”

“‘Terrorist hijackings, buildings blowing up, thousands of people dying — these are all things I’m accustomed to seeing,’ said Dan Monahan, 32, who witnessed the fiery destruction of the Twin Towers firsthand from the window of his second-story apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn. ‘I’ve seen them all before — we all have — on TV and in movies. In movies like Armageddon, it seemed silly and escapist. But this, this doesn’t have any scenes where Bruce Willis saves the planet and quips a one-liner as he blows the bad guy up.’”

Hanson: The events of 9/11 were the sort of a scenario where, if they had been fictional, they would have been really thrilling in a low-brow, bad, Jerry-Bruckheimer-movie kind of way. You could imagine Arnold Schwarzenegger being involved in a situation where somebody hijacked a plane and flew it into a building, or maybe Bruce Willis would be involved or whatever.

Harrod: My main memory is that Todd was really the MVP of that issue because he did both “Bruckheimer” and “God,” which were both excellent, filled with solid jokes and proper dealing with it. Both of those ended on poignant notes, interestingly enough, instead of a hard joke as would be normal for The Onion.

“God Angrily Clarifies ‘Don’t Kill’ Rule”

“Responding to recent events on Earth, God, the omniscient creator-deity worshipped by billions of followers of various faiths for more than 6,000 years, angrily clarified His longtime stance against humans killing each other Monday.”

Nackers: I think the piece about God was my favorite because I thought the satirical point worked on numerous levels. I liked it because it wasn’t about blaming one group, it was more about everyone at the time, both the terrorists as well as those rushing into war.

Hanson: The “God” one seems to be the one people remember the most, at least when they talk to me. That was my headline and that was assigned to me and I wrote it. I cried at the end of that story when God cries — I was actually crying. It wasn’t this cynical, dismissive, edgy humor that we normally would do. It was very sincere.

“Hijackers Surprised to Find Selves in Hell”

“‘I was promised I would spend eternity in Paradise, being fed honeyed cakes by 67 virgins in a tree-lined garden, if only I would fly the airplane into one of the Twin Towers,’ said Mohammed Atta, one of the hijackers of American Airlines Flight 11, between attempts to vomit up the wasps, hornets and live coals infesting his stomach.”

Krewson: The piece I ended up writing was “Hijackers Surprised to Find Selves in Hell.” It’s not the most advanced piece in the whole thing and I don’t think it’s the best piece in the whole thing, but it’s the most cathartic piece. I think it had a function to play. There was a lot of different stuff that we had to hit, and one of them was that everyone was angry. And there’s no question where these guys were going to end up. They were going to sit closer to the fire than Woody Allen but not that far from Hitler, you know?

“Not Knowing What Else to Do, Woman Bakes American-Flag Cake”

“‘I baked a cake,’ said Pearson, shrugging her shoulders and forcing a smile as she unveiled the dessert in the Overstreet household later that evening. ‘I made it into a flag.’”

Nackers: There’s really no one better at capturing American life and turning it into an amazing Onion joke than Carol Kolb. She really had her finger on the pulse of what Americans are like, and I think that’s just part of being a Midwesterner.

Mike Sacks, humorist at Vanity Fair, comedy writer and author of several books about comedy, including And Here’s the Kicker and Poking a Dead Frog: The one that captures it all for me was Carol’s headline, “Not Knowing What Else to Do, Woman Bakes American-Flag Cake.” There’s a sadness there that was very accurate to how helpless people felt.

Kolb: I think this story touched some people because it was more about personal grieving, as opposed to the more political headlines.

Hanson: That was based on our own Saturday night. Carol and I went over to a friend of mine’s and he had his neighbors over too, and the woman of that couple had made an American-flag cake. She was embarrassed about having done it and she felt a little silly, but she was like, “I didn’t know what else to do. So I did this,” and Carol wrote that up as a story. That wasn’t supposed to be making fun of the woman for doing it, it was just supposed to be sort of touching because it was a touchingly helpless gesture that happened to be from our real lives.

Nat Towsen, stand-up comic, comedy writer and fan of The Onion: One of my favorite things were the TV listings in that issue, which showed how different networks were adapting their programming. It was like a TV Guide schedule, and I distinctly remember the Nickelodeon ones like Clarissa Explains the Attack on America and SpongeJohn SquareAshcroft. I haven’t seen that issue in like two decades, but I still remember those.

Karwowski: Just about every network on 9/11 had news on it, even some non-news channels switched over to a news feed, except for one channel, which had Golden Girls. It was like news news, news, news, tragedy, tragedy, Golden Girls, tragedy, tragedy. So for this, I remember saying, “No matter what, I want one of them to be just a whole line of Golden Girls.”

Schneider: I think in the “News in Brief” section, you saw a little bit of the sharper humor that was more typical of The Onion. Like “Bush Sr. Apologizes to Son for Funding Bin Laden in 1980s.” You needed those reminders in there as to how we got to this point. Not everyone needed an emotional catharsis — catharsis can take the form of reason as well.

Nackers: There was a lot of care taken with this issue, more than any issue beforehand and any one since, really. We actually had some of the office staff — like our sales reps and office manager and people like that — come in and take a look at the jokes just to make sure we were being careful about what we were doing. We showed them this white board of headlines to get a non-comedian’s perspective, and it helped to have some outsider voices for such a sensitive topic.

Karwowski: A handful of people at The Onion who weren’t the writers had found out that we were going to do this issue directly about 9/11 and a bunch of people said, “If you do this, I will quit.” I can’t remember, but at least two or possibly three people said, “I will quit if you do this directly.” What we told them was, “Wait until we have the issue. We’re not going to be jerks about this.” Once we showed them and they saw how we were handling it, no one quit.

Hanson: That’s the weird thing. It was the riskiest issue we ever did, but we actually were really going tamer than we normally would.

Loew: We completed the issue and we were terrified that it would be greeted with derision or anger, and we’d be ridden on a rail out of town. That was a part of my mind for sure. I thought this might not work and that we might be headed back to Wisconsin.

Doing any sort of comedy so soon after 9/11 was exceptionally complicated and the stakes were no less high for The Onion. Not only was this their first issue back, but again, it was their first “New York City Edition” as well, meaning it was the first time The Onion would be available on newsstands throughout the city. So when The Onion sent their 9/11 issue to the printers, they had good reason to be concerned.

Sacks: Comedy right after 9/11 was really tricky. If you were involved in comedy at that time, it was a very strange time to be around. My own site at the time was the Fredonian and I just shut it down. Just about every comedy site did as well, like McSweeney’s and Sweet Fancy Moses. We just had nothing to say about it. It was a total shutdown of comedy.

Back then, as now, I worked at Vanity Fair and the editor, Graydon Carter, said that “Irony is dead,” which, even back then, I thought was ridiculous. Irony can’t be killed — we’re human beings — and The Onion staff would prove that irony wasn’t dead and they did it in a compassionate way, which was truly brilliant.

Siegel: There was a flood of think pieces about, “Is this the end of irony?,” “Is this the end of satire?” or “Is this the end of humor?” and “How can we ever joke again?” I remember spending a good portion of that week we had off supplying quotes to Newsweek and USA Today and all these publications that were speculating on the future of humor, which to me was absurd. Of course there’s going to be humor, especially since humor is a way of processing grief and pain and fear. If anything, there was more of a need for humor than ever, even if we maybe didn’t feel like it that week.

Karwowski: A few people did come back before us [notably Jon Stewart and David Letterman], but no one was trying to be funny at that point, so we didn’t know how this was going to go. All the talk shows at that time had very emotional reactions, and they were very gentle with how they approached the show. And we were just kind of like, “Well, we’re just getting back to normal.”

Sacks: Coming back, there was Letterman, who I remember talking straight into the camera, which I remember being very effective. He was talking about extremism, and I remember him saying, “I can’t understand anyone who would worship a god that would condone this.”

There was also, of course, Jon Stewart, who broke down on camera when he was talking about the Statue of Liberty. In some ways though, I look at it as The Onion coming back first because they dealt with it comedically first.

Schneider: Right after 9/11, all the hosts of comedy talk shows came on and were very somber. They didn’t tell jokes, they mostly did extended monologues with no guests, so people weren’t really making humor at that point and I think that drove our desire to do something funny. Not “too soon” type humor, but an alternate to how morose everything was.

Karwowski: Everything was so touchy at the time. Bill Maher got fired for saying something about how he found the terrorists to be brave, because they at least put themselves in danger, whereas the American military tends to bomb from afar — and he lost his show!

Krewson: There was also the Gilbert Gottfried thing, which was amazing, but I guess it seemed like a bit of inside baseball [because it was at The Friar’s Club]. That joke has only lasted the test of time because everyone else caught up with it and it’s become infamous.

Sacks: Gilbert Gottfried’s joke was classic because even other comedians were offended. Someone even yelled, “Too soon!” I mean, you’ve got to respect Gilbert for that, but I don’t really consider it a “classic 9/11 joke” — really nothing outside of The Onion fits that description.

Karwowski: Saturday Night Live [which came back on 9/29, after The Onion] started with Paul Simon playing “The Boxer” and then panning over the camera to the faces of firefighters and police officers and emergency workers, looking very still. Then Lorne Michael asks, “Can we be funny?” and Giuliani says, “Why start now?” So there was some humor in the show and there were sketches later on, but they started out by taking it very seriously.

Schneider: I understand it though. For a talk show or comedy show, a break from the frivolity made sense, but given that we were The Onion and that humor is what we do, I think if we did it straight, it wouldn’t have had the impact.

Siegel: It was definitely easier for The Onion to come back because of our format, really. Because we’re this deadpan, satirical newspaper, it was somehow less disrespectful than, say, Letterman and his standard format.

Hanson: Most came back and didn’t do comedy, and while people say we were brave for coming back, the Upright Citizens Brigade was on stage that night downtown, and Marc Maron was too — he was on stage that night doing material about the events.

Sacks: The ones who came back with satire were The Onion, which was so necessary at that time. They could have waited or they could have gone back to Wisconsin because they were all still pretty new to New York, but they faced the issue head-on. Their format was perfect for this too, because it allowed for multiple voices and this was a news story, so this format was much more conducive to taking a shot at the situation.

If you look at it now, it’s very gentle. It wasn’t the typical The Onion necessarily, but they kind of crept back into it in the perfect way. Comedy fans especially needed a first take on it. We needed someone to say, “It’s okay.” Not to make fun of the situation, but to make fun of our anguish and our confusion. It was a real fine line. There really was no margin for error. They really had to stick the landing, and they stuck it. Honestly, being in comedy at that time and being with many who felt a bit lost as to how to approach it, The Onion really showed all of us the way.

The Onion’s 9/11 issue would arrive on newsstands on September 27th. The first reply came via fax, and it didn’t exactly alleviate anyone’s fears that the issue might be their undoing.

Hanson: Everyone came to work that day, terrified of what was going to happen. In my mind, I was thinking that this may be the last issue that The Onion ever publishes. Our audience may turn against us. We may lose all of our advertisers and everybody would hate us and we’d go out of business. It really felt like everything was on the line.

Joe Garden, writer from 1993 to 2012: The day after the issue went up online, we came into the office — late, as usual — to a fax that just had the words “Not funny” written over and over on it. I thought that didn’t portend anything good.

Krewson: That top fax said, “not funny, not funny, not funny” in huge writing, but below that was a stack as thick as a phone book and just about 98 percent of it was all praise. We got stuff from U.S. military bases, stuff from police departments. We got stuff from families of people who were involved. It was nuts. Somewhere in my files, I have an article about a woman who came to our party the night before and was so hungover that she wasn’t able to get to work at the World Trade Center the next day.

Loew: Maybe we saw four or five emails that were like, “How dare you make light of this tragedy?” But then we got a phone book’s worth of emails praising us. We printed them all out and put them in a binder. The response was overwhelmingly positive. So many people said that this was the first time they’ve laughed in weeks, and people were emailing us who had lost coworkers and family members and they were thanking us for making them laugh again. We also got a few emails from people that had hung out with us the night before who told us that, because of The Onion, they were late to work the next day at the World Trade Center.

Karwowski: Usually we got around 50 or so emails from people for an issue, but for this issue we were getting thousands of emails and I’d say 95 percent of them were positive. Every once in a while you’d get someone who was like “too soon” or “inappropriate,” but most people were like, “Thank God, it’s been two weeks of everyone taking things so seriously.”

Harrod: I remember the giant, “not funny” sheet being passed around until John Krewson had it in his hands and he looked at it and went, “Huh, interesting” and then he crumbled it violently in his hands then threw it away. A couple of us started yelling at him like, “Hey, that’s an artifact of this issue! That might go in a museum someday!”

Kolb: It felt good to get all of these emails that said “I needed to laugh,” and it was so much more important that the normal replies like, “That was so funny dude!” that we’d normally get. In this very difficult time, it just felt wonderful that people were actually moved and thankful to have an opportunity to laugh.

Hanson: Not only were the responses good, but there were things like, “God bless you” and “Thank God for The Onion” and “God bless The Onion.” I don’t remember anybody even thinking that was even a possibility. So we were quite blown away and quite emotionally humbled by it. We were really touched that anyone would react that way. It was just deeply, deeply moving.

I remember one story I heard later on was especially touching. It was from a guy named Nat Towsen, who was a high school student at a nearby high school during 9/11 and his school was evacuated from the area during the whole thing. I met him once and he told me how much The Onion meant to him at that time and how important it was to him and his friends.

Towsen: I was a junior in high school in 2001 and I went to Stuyvesant, which was down the street from the World Trade Center. I was in school the morning it happened, and my school was evacuated and the students and teachers began marching up the West Side Highway for our parents to pick us up farther uptown. I lived in Greenwich Village, and once we all reached Houston Street, I told one of the guidance counselors that I lived here. He told me to go and take as many of my friends with me as I could.

There were problems with the phone but we were able to use the internet line to contact all of my friends’ parents and they were picked up one by one. My grandpa also came down and brought us all pizza, though I had missed him myself because a few of us had left the apartment to bring water to some of the first responders. More than that, I don’t really remember much about the day of. I can’t remember my dad or my brother coming home, I just remember my last friend leaving and that’s about it. It’s still kind of hard for me to talk about.

I was already a fan of The Onion before 9/11. My best friend had brought a copy of The Onion’s Our Dumb Century to a pre-high school orientation event and showed it to me. So we were following it on the internet from the beginning of high school and then he got a print subscription for Christmas. We also used to go to the school library and print out The Onion articles — I’d keep them in my backpack.

For the 9/11 issue specifically, it distilled the hypocrisy surrounding 9/11 perfectly. This was during the golden age of The Daily Show, but I’d still say that The Onion had reliably the best take out there, largely because the mainstream media had all this jingoistic bullshit everywhere.

See, for the people who lived in New York, 9/11 was a very different experience than it was for the people who didn’t. It was a very personal thing that happened and it happened locally, and the mainstream media took the narrative away from us very quickly. All of a sudden, it was this thing that happened to America and we had to be “strong” and “patriotic” and “support the troops” — all of these things that didn’t reflect our experience as New Yorkers.

The Onion, though, seemed to be a voice of reason that was shining a light on all this bullshit, both in the 9/11 issue and their coverage afterwards. Later on, when you could find them for free in newsracks in the city, I used to grab a stack of them and distribute them around my high school because I wanted more people in my school to read it, in part because I wanted to talk to people about it, but also because it just seemed like a voice of reason when the official channels were spouting so much hypocrisy. It was also much more cutting and insightful than the late-night shows my parents were watching. I felt like The Onion was something I really needed at the time when I was just a powerless high schooler, because The Onion had a voice when I wasn’t able to have one.

Siegel: People were saying they were cracking up, but if you look at what they were reacting to and laughing at, it wasn’t really jokes. It was just a kind of expression of our collective experience. We just put a voice to what people were feeling and expressed how scary and horrible and fucked up and dark it all was.

Krewson: It was a couple of years later that we learned that the rumors were correct and that we had actually been suggested for a Pulitzer.

Sacks: I really think they deserved the Pulitzer for that, and it’s a shame that they didn’t get it.

Jim Romenesko, excerpt from Poynter article “Philly Editor Thought Onion’s 9/11 Issue Was Pulitzer-Worthy”: The Pulitzer judges “were blown away” by The Onion’s first issue after the 9/11 attacks, “but it was a little too different, a little too risky,” says Philadelphia Daily News editor Zach Stalberg. “I voted to make it a finalist, but nobody else did.” The rejection highlights what some feel is the reverence — some might say restrictions — under which the Pulitzer judging operates, says Joe Strupp.

Schneider: I do remember getting a lot of praise and compliments for the issue, though I do think the legend grew a bit over the years. At the time, it was just appreciated, but we had to go back to work and keep turning out issues. We got good feedback, but we kept our heads down and got back to it, which was the nature of putting The Onion out weekly.

While many found the issue to be cathartic upon its release, as the years have passed, the issue has stood the test of time as a great work of satire. Its legacy has been felt both at The Onion and elsewhere.

Nackers: I think starting with the 2000 election, where the Supreme Court chose the president, we started to go into a harder form of satire, which led very naturally into what we did in the 9/11 issue. After that point too, people were just consuming more news, and from there, you go into the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. So it’s a darker time for our country. There are other factors too, though. Now you have an entire generation growing up who didn’t get print newspapers — we stopped doing print in 2013 — and that changes things as well. Also, we don’t have “issues” like we did. Now if something happens, we have a story up about it an hour and a half later. Now there are less silly headlines and more of us just ridiculing the problems of society.

Kolb: Over the years, when I’ll mention that I worked at The Onion, people will ask if I was there for the 9/11 issue. I guess, in a way, I’m not surprised that people are still talking about this issue 20 years later. If you’re someone who is into humor and comedy — and because 9/11 was a huge part of history — it makes sense that it would still be a topic.

Hanson: I’m still surprised by the fact that it’s remembered as it is. There was a big cable series about the decades not long ago and somebody — maybe CNN or BBC or National Geographic, I can’t remember — brought me in and put me in a room with cameras around me and interviewed me about the 9/11 issue because they were including the 9/11 issue as part of the events of that decade. It was an appropriately tiny part of the special, but it was included as something defining the fucking zeitgeist of the decade, which still blows my mind.

Krewson: I’m fucking shocked that people are still talking about it 20 years later, frankly. I wasn’t a major writer for it. I think I just had a few things in there, but I’m as proud of that as I am of anything I’ve done in my life. As for why it was such a success, I don’t know, but I think it comes back to that thing George Bernard Shaw said: “Life does not cease to be funny when people die any more than it ceases to be serious when people laugh.”

Harrod: If you’re really going to be a satirist, you have to walk into the horror and acknowledge it. MAD Magazine holds an important stature in the history of that, but it also has arguably watered down the word satire to where it seems to mean any parody. But satire is a very specific thing — like what Jonathan Swift did with A Modest Proposal. Swift acknowledged the horrors, which is what I think we did with this issue.

Sacks: Having looked at the issue again recently, it really holds up and it’s just a classic piece of written comedy, along with the National Lampoon High School Yearbook, Michael O’Donoghue’s The Vietnamese Baby Book and MAD Magazine in the early days. I think the fact that it was in print gives it something special, too. Like A Modest Proposal, which was a leaflet, this was something you could hold in your hands, which is something we don’t have anymore in the same way. This is a real piece of history and that staff was really something else. Written comedy usually goes bad so quickly, but this one will continue to stick around.

Siegel: I’m really proud of the whole thing, but I’m more proud of the reaction than the actual thing itself. I’m happy people think it was brave and bold and brilliant — I’ve been told it’s those things. I feel like it was more that we were tapping into something so powerful that it was more about the hugeness of the event, which is what made it probably feel bolder and braver than it was. We were just doing what we did every week, and we had to do it to keep the lights on in the office.