Because Good Boys is a proudly vulgar, R-rated comedy produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, the guys behind the raucous and rude Superbad and Sausage Party, it’s natural to assume that the title is meant to be ironic. But what turns out to be pretty delightful about this good-enough film is that its three main characters are, in fact, good boys. We’re used to broad comedies where the young men are immature, horny overgrown adolescents. Good Boys’ great, subversive running joke is that actual boys, in some ways, are much better than their older counterparts — at least on the big screen. Beyond being consistently funny, the movie is oddly poignant: Please, lord, don’t let these sweet kids grow up to be asshole men.

The film follows the Superbad/Booksmart template, introducing us to friends on a mission to get to a blowout party. As opposed to those other films, though, the characters’ ages — and therefore the stakes— aren’t as high. Max (Jacob Tremblay), Lucas (Keith L. Williams) and Thor (Brady Noon) are sixth graders, and as such, they have only the faintest understanding of the adult world. They’ve never had sex — they’ve never even kissed a girl — but they’re mortified that anybody in their school might find out, so they lie and claim they’ve done both. But when Max learns about a classmate’s shindig, where he might be able to kiss his secret crush Brixlee (Millie Davis) — because he’s just a kid, he doesn’t just think she’s his true love, he’s convinced they’re going to get married — he becomes determined to get there.

Complications ensue — really, really dumb complications — and in general, you’re better off ignoring Good Boys’ plot, which is generic and convoluted all at once. Really, the story is simply an excuse to watch these three boys get into mischief, which they react to in amusingly relatable kid-like fashion. One of the reasons why teen comedies like Superbad or American Pie never entirely worked for me is that I wasn’t one of those teenagers: sex-crazed, gross and lovably dumb. But I was definitely like the kids in Good Boys, who are anxious to gain access to adult stuff but are so ill-equipped to handle it that they mostly stumble over their own feet. The movie never lets you forget that most boys aren’t hip, zany or cool — they don’t come with a prepackaged identity. Instead, Max, Lucas and Thor are just little unformed pseudo-humans struggling to figure everything out and failing badly.

It all starts with the casting. Max is a cutie-pie who’s recently discovered masturbation but hasn’t turned into a weirdo cretin because of that fact. Thor loves musicals but is embarrassed by his incredible singing voice because he thinks it makes him look unmanly. And Lucas is struggling because his parents just told him they’re getting divorced. We’re used to seeing wild-and-crazy-and-edgy young people in teen comedies, but Max and his buddies aren’t that advanced yet, and the three actors — who are all around 12 or 13 themselves — believably play their characters’ guilelessness and naivety.

Director Gene Stupnitsky, who wrote the screenplay with frequent collaborator Lee Eisenberg, gets all the little details of boyhood right. When Max, Lucas and Thor have their predictable falling out around the end of Act Two — y’know, so they can reaffirm their friendship during the movie’s feel-good ending — they get so mad at each other that they start crying, just the way kids do when they’re upset. When they discover porn, they’re both utterly confused and a little grossed out. (Why is she putting her mouth… there?!??) And because they’re still at an impressionable age, the boys are so anti-drug that they’re practically a walking “Just Say No” ad, parroting the language they’ve no doubt been taught in school. (Good Boys’ lame plot involves them accidentally gaining possession of some high school girls’ Molly. But the boys aren’t interested in partaking — instead, they panic and lecture the teens about how they’re addicts who are throwing their lives away and destroying their community, using the hilariously strident language of a bad PSA.)

If Good Boys was simply a collection of gags about how boys don’t understand the adult world, it would be fitfully funny. But what elevates the film and makes it oddly moving is its appreciation for how kids haven’t yet adopted the meanness and cynicism that comes with age. In these kids’ school, there are jerks and bullies — it’s not a sanitized movie world — and it’s clear that Max, Lucas and Thor are among the nerdy. (They play role-playing games and think it’s rad to call themselves the Beanbag Boys… because they have beanbag chairs.) But while these boys long to be cool — which means taking more than three sips of beer, a middle-school record! — they’re not interested in becoming assholes in the process. As they go on this crazy journey, they never posture as badasses — they never treat people badly.

And what’s striking is that many of the older boys they come across absolutely do. One of the Molly teen girls has a boyfriend who is awful to her, preying on her insecurities. At one point, Max, Lucas and Thor confront the boyfriend at his fraternity, where they encounter plenty of other shithead men. Even Thor’s supportive musical director is a deluded cokehead. Outside of their dads, these kids don’t have a lot of great male role models, and yet, the boys’ kindness carries them through their misadventures. Max and his buddies are adamant that women should be treated with respect — although they sometimes take it a bit far, endearingly. (When Max does finally kiss Brixlee, he first asks for her consent in a formal, chivalrous manner.) In Good Boys, we’re light years removed from the cruel manipulations of a Porky’s, where women were treated like dumb sex objects ripe for the plucking, and thank god for that.

On the one hand, you could argue that the filmmakers couldn’t have a movie where tweens get drunk, screw and trip balls — the protests would be vocal and legion. But on the other, Good Boys is a surprisingly optimistic view of the next generation of young men. Life has a way of hardening people, beating their sweeter tendencies out of them. But Max, Lucas and Thor operate in a universe where bullying is self-policed and asshole bros get shown up by the nicest middle-schoolers you’d ever hope to meet.

Maybe Good Boys is a bit of a fantasy. But it also poses an interesting challenge to lots of older guys who will be able to see this movie because it’s R-rated: You were probably this innocent and kind back then, too — what happened?

Here are three other takeaways from Good Boys…

#1. Amazingly, no one knows how “Spin the Bottle” started.

The big party in Good Boys has, as its main attraction, a group of tweens playing “Spin the Bottle,” including Max’s beloved Brixlee. I’d be curious of the ratio between actual human beings to play that game versus the amount of movie characters who do. (I never played it, but it pops up in films a decent amount.) And I was also curious just how the game started. Basically, who invented “Spin the Bottle”?

To my surprise, the internet doesn’t seem to know.

On Wikipedia, there are suggestions that “Spin the Bottle” may have derived from bottle-spinning games of the 1920s, although the kissing element may not have been crucial to those earlier iterations. Someone on Quora speculated that the game could have been an offshoot of Rota Fortunae, or “the Wheel of Fortune,” an ancient instrument that supposedly determined individuals’ fate. But there’s nothing definitive anywhere online, just guesses.

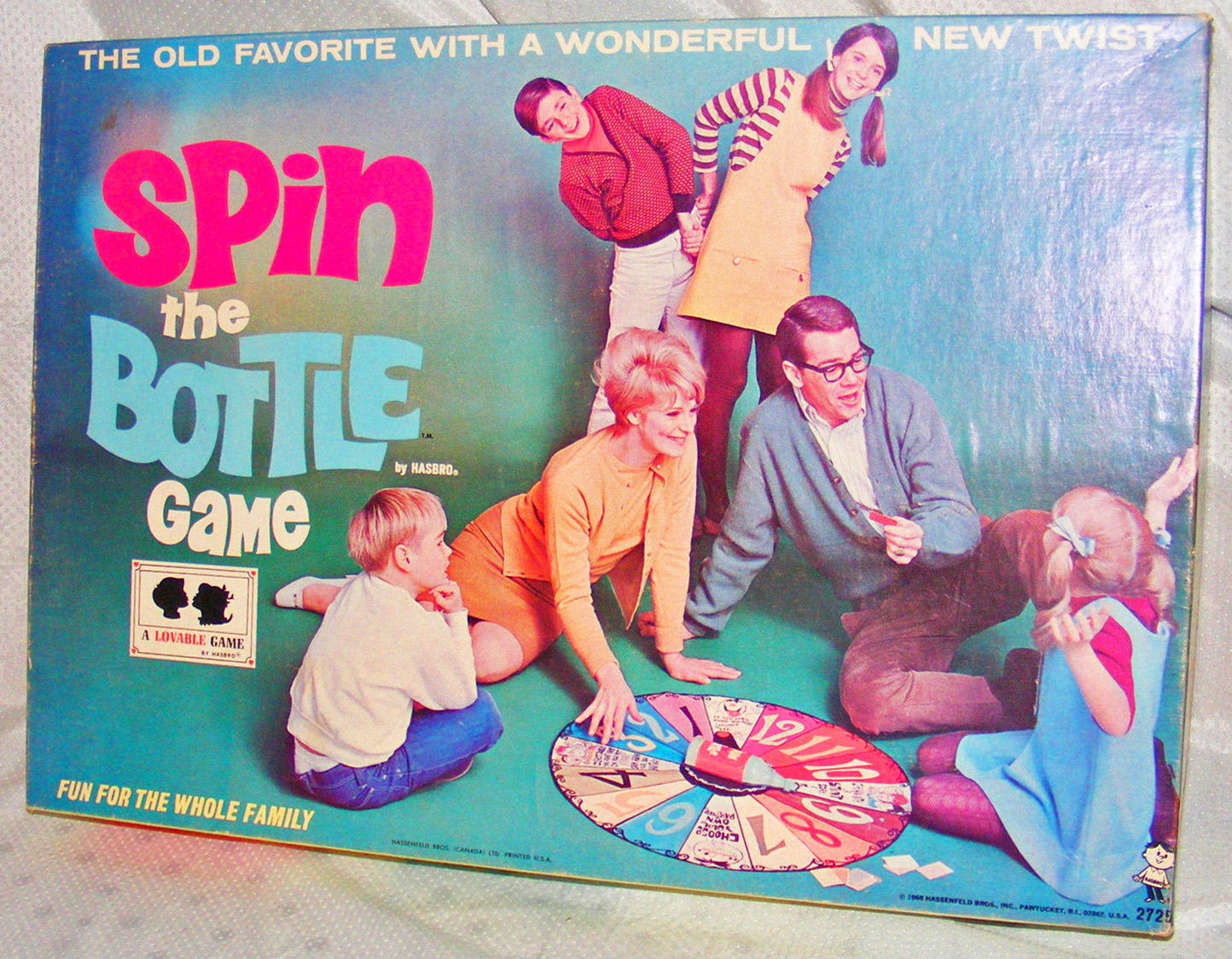

However, in my research, I did stumble upon something incredibly upsetting: In the late 1960s, Hasbro put out a family-home-game version of “Spin the Bottle,” which you might assume would not involve kissing. Well, no, but it’s still pretty creepy. Best as I can tell, you have to follow instructions on cards that must be performed with members of the opposite sex. One of the cards directs you to “Make your partner blush, using any means available to you except physical contact.”

Listen, the whole point of family game night is to be around people with whom you have a difficult time discussing intimate matters like sexuality. The amount of therapy I’d need after playing Hasbro’s game with my brood would have bankrupt me.

#2. The MPAA’s rating description for ‘Good Boys’ is adorable.

Like all studio films, Good Boys is assigned a rating by the MPAA’s Ratings Board, along with an explanation for why the movie is rated what it is. Since I’m a childless adult, I rarely pay attention to the MPAA explanation, but I happened to notice the one for Good Boys, and it made me laugh: “Strong crude sexual content, drug and alcohol material, and language throughout — all involving tweens.”

All involving tweens!

Sadly, the Ratings Board website doesn’t have a search function that allows you to check how many times the word “tweens” has shown up in a ratings description. So I decided to just throw in some titles to see what happened. Booksmart, which was also rated R, got the rating because of “strong sexual content and language throughout, drug use and drinking — all involving teens.” Superbad was rated R “for pervasive crude and sexual content, strong language, drinking, some drug use and a fantasy/comic violent image — all involving teens.” But it’s not always R-rated films where we’re warned about the youths: 2012’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower was awarded a PG-13 “for mature thematic material, drug and alcohol use, sexual content including references and a fight — all involving teens.”

It appears that Good Boys is the first film to earn the “all involving tweens” distinction. As others have noted, the MPAA is sometimes laughably meticulous about making sure we know what teenagers are doing in movies, like partying or fucking, and so the Ratings Board will include a mention in its ratings explanation. There are many reasons Hollywood’s ratings system is terrible — rampant violence is far more acceptable than even the tiniest whiff of nudity or sex — but the board’s prudish monitoring of a film’s teens and tweens is definitely one of them.

Obviously, these distinctions exist to warn parents about potentially upsetting Fictional Young People Behavior: Just imagine if a kid saw something untoward in a mainstream comedy! But it does bring to mind a question: What separates “pervasive crude and sexual content” from “strong crude sexual content”? Just how “pervasive” does my crude sexual content need to be?

Man, these Ratings Board people sure seem like they have sex on the brain.

#3. Here’s the moment in the movie that made me really uncomfortable.

So, after just mocking the MPAA, I’m going to turn around and be all nanny-state about the one sequence in Good Boys that gave me pause. At one point, our wee heroes need to get to a mall. The problem: A busy freeway stands between them and the shopping center. Initially, all the cars are backed up, making it easy for the boys to cross, but soon the traffic jam ends, leaving them having to execute a mad dash to get the rest of the way there.

Obviously, a sequence like this is supposed to be shocking. (This is an R-rated comedy, after all.) But unlike the rest of Good Boys, whose humor is pretty believable and human-scaled, this freeway dash is flat-out preposterous. Once the traffic jam ends, there is no way those kids would make it across the road alive. (There are several YouTube videos of people being hits by cars I will do you the favor of not linking to, but trust me.) And while I’m sure I come across as a fuddy-duddy, I actually think the scene is borderline irresponsible.

Look, lots of crazy physical comedy occurs in studio movies these days. People get thrown into houses, launched off horses, catapulted into the sky and so forth. We’re meant to understand that it’s all slapstick and not realistic. But while Max, Lucas and Thor could survive that ordeal.

I think my hang-up comes from my own anxiety about driving: I’m constantly terrified that, out of nowhere, a kid will jump out into the street before I can brake. In L.A., I see enough Drive Like Your Kids Live Here signs that I’m on high-alert at all times. Truth is, I live in fear of one day hitting a kid — or any pedestrian, really — and I don’t know if I’d ever live down the guilt of my action. So thanks, Good Boys, for being extremely triggering. The Ratings Board didn’t properly prepare me for that.