In 1993, the comic book industry was headed for disaster. 1992 was the biggest year ever in the comic book collector’s market, but rather than see the record sales for the bubble it was, comic book companies continued to pump out more and more titles for people to collect. For Marvel Comics specifically, they were dishing out 140 monthly titles in 1993 — up from just 50 books in 1988 — and in late 1993, the industry hit a breaking point. Over the next couple of years, comic sales plummeted 70 percent and 90 percent of comic shops shut their doors. In 1996, Marvel filed for bankruptcy, which would nearly collapse the entire industry.

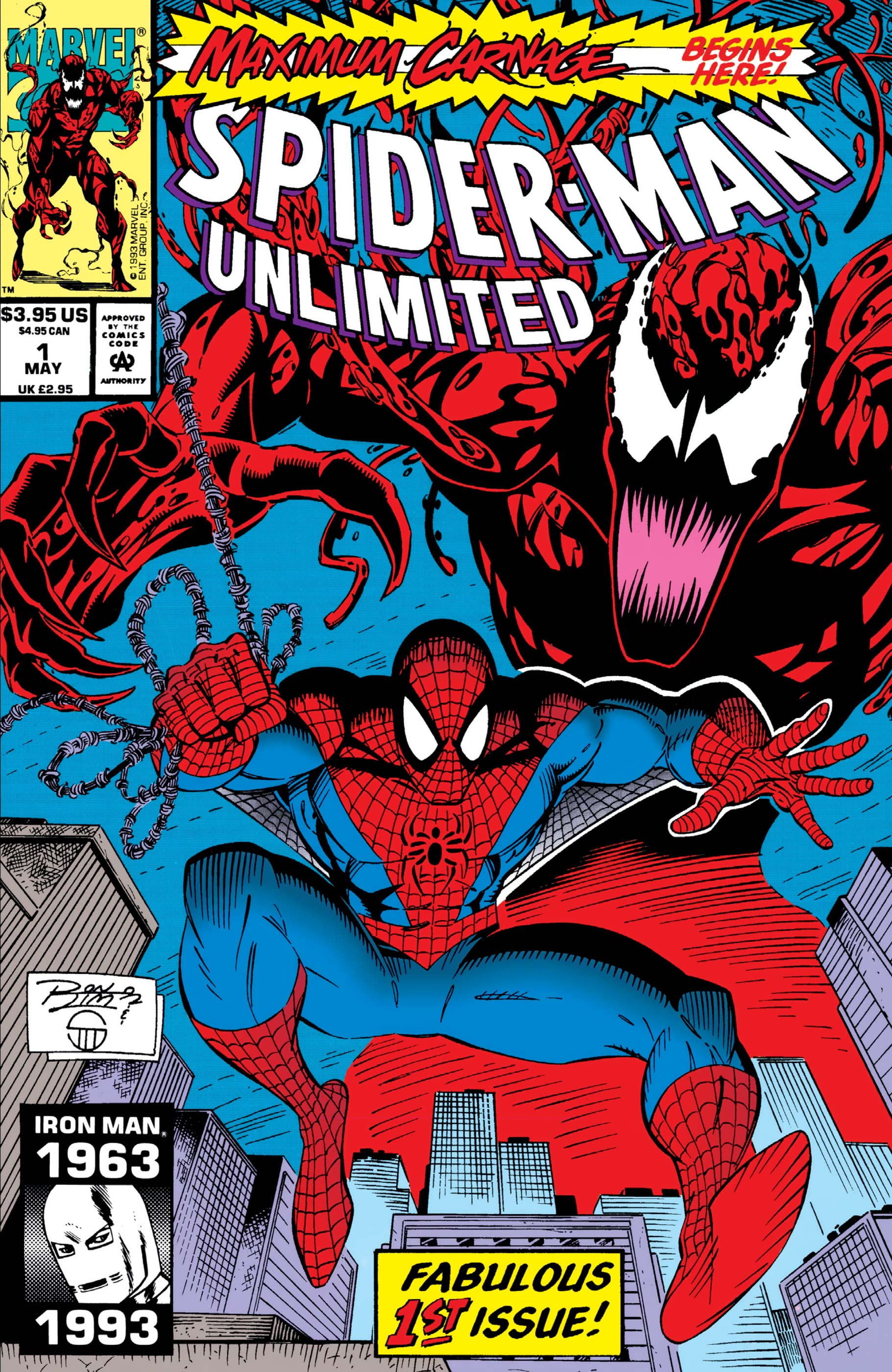

Just before all this, though — right at the cusp of comics’ near-apocalypse — was the (arguably) classic Spider-Man crossover event, Maximum Carnage. The 14-part saga began in May 1993 and lasted until November, spawning a media blitz like nothing before, including action figures and a very popular video game. Twenty-seven years later, the saga is still one of the most identifiable Spider-Man stories of all time, so much so that when the title of the Venom sequel film was recently announced — Venom: Let There Be Carnage — fans took to social media to ask why the already-famous “Maximum Carnage” name wasn’t used instead.

So what was the big deal about Maximum Carnage?

Reading the book now, it comes off as something of a time capsule for early 1990s comic books. While it stars iconic characters like Spider-Man and Captain America, it also includes a great number of characters who would seldom be seen again after this crossover. The storytelling and the artwork boast many of the “extreme” elements that made 1990s comic books both notable and, later on, a cliché. As a character, Carnage himself pretty much sums up what those 1990s trends were all about, being excessively violent, inhumanely evil and visually striking. But to understand Carnage, it first helps to understand the characters who directly led to his creation — namely Spider-Man and Venom — and where these characters were in 1993.

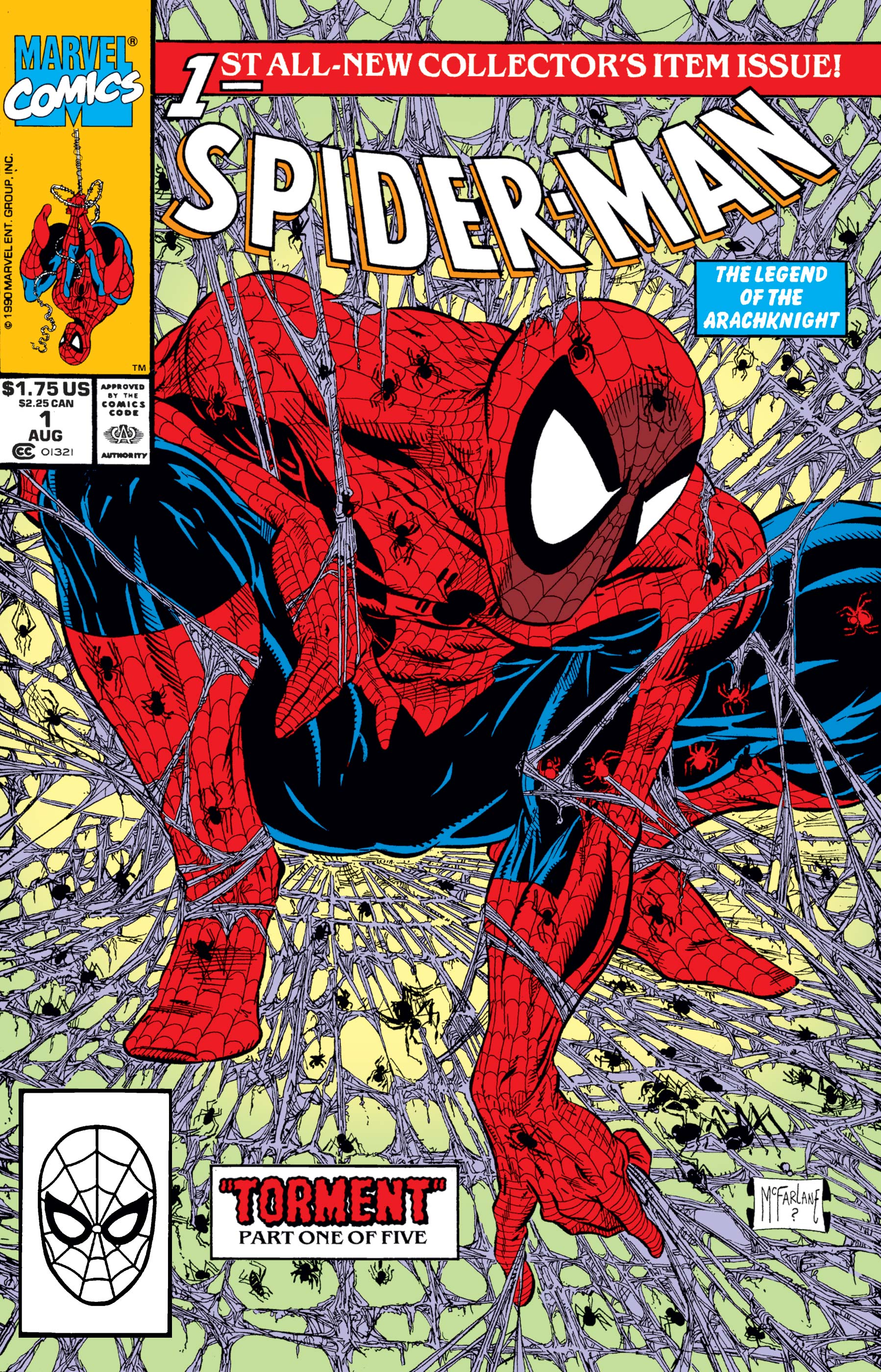

Spider-Man

Dan Wallace, author of the 2006 edition of The Marvel Encyclopedia: In the 1980s, comic books were a bit more writer-driven, but in the 1990s, it became more artist-driven. For X-Men, it was probably Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld, and for Spider-Man, it was Todd McFarlane. That’s where the interest in Venom and Carnage kind of came up, when Spider-Man got this jolt of new life thanks to McFarlane’s interesting, fluid style, which really was revolutionary at the time. So even though McFarlane was no longer doing Spider-Man by the time Maximum Carnage came around, I think that era owes a huge debt to McFarlane. He really juiced Spider-Man and that popularity remained for a while after he left.

J.M. DeMatteis, writer with Marvel Comics and animation, 1980 to present: By the time Maximum Carnage came around, I’d been writing Spectacular Spider-Man for two years. Back then, Spider-Man had just gone through his ultimate, heartbreaking battle with the Harry Osborn version of Green Goblin. It was a battle that left him in mourning for Harry, who was Peter’s best friend at the time. When he died, Harry had proven himself to be a true hero, saving Spidey’s life, so Peter was very raw and vulnerable going into this story.

Venom

Toy Shiz, toy collector and Spider-Man fan: Venom is such a complicated story now, but it was simpler back then. Back in the 1980s, Spidey went to space and he got this other costume because his costume got destroyed and it turns out it was a living symbiote, then Spider-Man goes through all this stuff. Eventually, you get to Venom once the symbiote gets on a guy named Eddie Brock, a disgruntled reporter who hates Peter Parker. While we were used to Venom as a villain trying to kill Spider-Man all the time, by Maximum Carnage, Venom was just being introduced as a hero — a “lethal protector” — like he’d be later on in the movie and everything else.

Carnage

Matt Forbeck, author of the 2014 edition of The Marvel Encyclopedia: Carnage was a character that was reproduced off of Venom, but while Eddie Brock was a disgruntled journalist, Carnage was a serial killer, so instead of the anti-hero Venom became, Carnage was a full-on badass serial-killing villain.

Wallace: During this time, you had a lot of new characters that were more “extreme” and “edgy.” Some may disparage them now as really “‘90s” characters, but they were really fresh at the time. Carnage, in particular, is a product of the 1990s, and I think that’s clear due to the violence of the character and because he’s just a more extreme version of Venom, who was already kind of extreme. Carnage was very much a “turned up to 11” kind of character.

Bob Sharen, colorist at Marvel Comics, 1978 to 2001: I always thought Carnage was a ridiculous character. I don’t know why fans are interested in him lately.

Tom DeFalco, Marvel Comics writer and editor, 1980 to present: Carnage was one of the great aggravations of my life. When Carnage first came out in 1992, I was editor-in-chief at Marvel. I remember walking into my office and my secretary says that a bunch of retailers have been calling and that they’re all really pissed. I wondered, “What the heck are they pissed about?” and as I’m standing there, another one calls and she tells me, “That’s another one, and he’s really angry.” So I told her to put him through and I took the call in my office.

The first appearance of Carnage had just come out the day before and this retailer was furious, telling me, “The new issue of Spider-Man came out, and I’m completely sold out already.” I was kind of befuddled by that, so I said, “Isn’t that a good thing?” But he tells me, “All my customers are angry because I’m sold out because you didn’t tell us that you were introducing a new character who was going to be so popular!” Of course, we have no idea who is going to be popular and who isn’t — we introduce new villains all the time!

So he asks me if we were going to go back to press on that one, and in those days, it was rare to go back to press on a comic book, so I said, “I don’t know.” Then I went to the sales department, and they were getting screamed at by their retailers and the distributors, because this thing had sold out. So we decided to go back to press and we got numbers from the retailers for how many they needed. I don’t remember the number, but once they told me how many copies the retailers were requesting, I said, “Double it!” As they were preparing to reprint, the calls kept coming in and the number of orders reached my doubled number, so I told them to “double it” once again. That print run lasted two days, and we had to go back to print a third time, which also sold out.

Carnage proved to be even more popular than Venom and that caught us all by surprise. Venom had bigger legs and stretched out for much longer, but the initial launch of Carnage was much larger than Venom. [Writer] David Michelinie really struck gold twice, as he created both characters, with Venom being designed by Todd McFarlane and Carnage being designed by Mark Bagley.

Creating ‘Maximum Carnage’

A year after Carnage’s huge debut, Marvel knew that they wanted to capitalize on the character’s popularity, so group editor Danny Fingeroth — who oversaw all of the Spider-Man titles — began making plans for a multi-title crossover event.

Danny Fingeroth, writer and editor at Marvel Comics, 1976 to 1995, and author of A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee: As I recall it, Maximum Carnage more or less originated with me. Eric Fein, an editor in the Spider-Man group, came up with the title, as well as the name of the character Carnage in the first place. This was the era of the big crossover, where people did multi-part crossovers within a family of books and I wanted to do something like that, in part to compete with the X-Men books. We were also kicking off Spider-Man Unlimited, which was a quarterly, giant-sized Spider-Man title, and I knew a crossover was a good way to promote that book, so Maximum Carnage began in Spider-Man Unlimited #1 and concluded in Spider-Man Unlimited #2.

At the time, I was interested in the fact that we had so many characters who were really villains, but sort of were being treated almost like heroes, like Venom and The Punisher. So I made a list of characters who were clearly villains — like Carnage — and then I made a list of the characters who are clearly heroes and generally had a non-killing code, like Spider-Man and Captain America. Then there were “gray area” characters like Venom who were heroes, but didn’t have this absolute code against killing. I wanted to do a story that laid out the ethical and philosophical differences between these characters. And, on a purely commercial level, I knew that Venom and Carnage were incredibly popular, so I wanted to use Venom and Carnage.

That was the basic premise, which wasn’t much of a story yet. It was just a way to align characters, and that’s what I brought to my writers and artists.

Alex Saviuk, penciler at Marvel Comics, 1987 to present: Back in 1992, I had just moved to Florida, and I got a call in early December from Danny Fingeroth, who said, “We’re going to fly you up to New York; we’re going to meet at this hotel and everybody that’s involved with Spider-Man — all the editors, writers and artists — are meeting for a two-day powwow.”

DeFalco: Working with those guys was a tremendous amount of fun. Aside from being Marvel’s editor-in-chief at the time, I was also writing Thor and Fantastic Four, so when Danny came to me and asked me to write Spider-Man Unlimited, I initially turned him down, but it was such a blast being with all of those guys that I got roped into it.

Throughout that meeting, we kept saying, “How do we make this even more interesting? How do we make this even more exciting?” And that was our goal — just to try to do the biggest, most exciting story we could.

DeMatteis: I recall that it was a great bunch of people — Tom DeFalco, David Michelinie, Terry Kavanagh, Sal Buscema, Mark Bagley, Tom Lyle, Alex Saviuk, Ron Lim. There was a free-flowing expression of ideas and no big egos getting in the way. No one claimed their ideas were precious and untouchable, and each one of us was respecting the others. It was fun! Danny and company always ran great meetings and really encouraged us to have a good time while we hashed these stories out and we really did.

Fingeroth: We were in a hotel conference room in Midtown Manhattan and everybody was making a lot of noise — shouting ideas for characters and scenes and plot points — then the phone rings and it’s the front desk of the hotel. They say to me, “We’ve had a complaint from the meeting next door. They say you guys are making too much noise. Could you please tone it down?” I went, “Sure,” but, of course, I was thrilled. As the group editor, it was the most gratifying thing to have people that excited about what they were putting together.

The Process of Making Comic Books, Circa 1993

Once the 14-part event was plotted out, the writers and artists got to work on what would become some of the most reprinted work of their careers. While the creation of comic books today is digital on nearly every level, back in the early 1990s it was a painstaking analog process, broken up amongst many different collaborators.

DeMatteis: Danny was the hub around which the wheels of the crossover turned. Without someone overseeing a story this big, the whole thing can just fall apart.

Fingeroth: When you’re doing a 14-part story being written by four different writers, it’s important that you have at least a basic outline. That way, “Writer B” knows that he has to start his story where “Writer A” left off.

Kavanagh: There was almost like a “beat sheet” us writers had where it would lay out the major story points, and then we’d fill in specific details. We’d always be given the plot from the previous chapter before we could start writing our own. A writer would write something and hand it into the editor, who might ask for some changes, then the writer would make the changes, it’d get approved and then the editor would give it to the other writers.

Saviuk: The pencilers would have to coordinate a bit too. I would get the Xeroxes of the [issue] before mine so I could see how things ended, so that I would know where mine began, then the next penciler would get my Xeroxes for the following issue.

Scott Hanna, instructor for and co-founder of The Arts and Fashion Institute, inker at Marvel Comics from 1992 to present: Well, that’s how it was supposed to work, but on Maximum Carnage it wasn’t always so well organized. I was inking for penciler Tom Lyle — who was a dear friend and a great artist who passed away last year — and Tom would often be basing his last page on the next issue’s first page that someone else already drew, instead of the other way around.

Saviuk: Marvel had a particular plot style going at the time that Stan Lee had originated, but every writer did this a little bit differently. Some gave the penciler a script with numbered panels, while others gave me more freedom where I’d get a paragraph for every page of the story, so it was up to me to decide how many panels to use. I worked at home mostly, and after I had those penciled pages, I’d send them to Marvel via FedEx. Then they’d make some Xeroxes of those, and a Xerox would go to the writer to write the dialogue while my pencils would be inked by the inker.

Hanna: The inker has always been the most misunderstood role in comic books. See, a comic book is a monthly product, and if a comic book is late, there is a big penalty from the printer. So, they came up with a system long ago where they divided the art chores: The penciler would do the initial drawings, a letterer did the word bubbles, an inker would finalize the art and a colorist would provide the color. This allowed for more of an assembly line process to get the books out more efficiently.

In my role, once I received the pencils, I would finalize the art and do the light and shadow and take care of many of the details, like drawing the webs on Spider-Man’s costume — that was my job. Also, in a big crossover like this, if Spider-Man’s mask gets ripped in one issue, it has to have the same rip in the next issue, but with everyone drawing these issues at once, it became the inker’s job to keep track of continuity via Xeroxes and by personally going into the Marvel offices to see these pages.

As for lettering, by the time I was working on Maximum Carnage, lettering was done separately and then the balloons were pasted onto the page after the inks were completed. That means that lettering was usually done at the same time as the inks, based on Xeroxes of the original pencils.

Rick Parker, Marvel Comics letterer and artist from 1977 to 1996: I don’t remember working on Maximum Carnage. If I lettered it, it made zero impression on me.

Lettering was a great job though and it’s kind of a lost art now. I started at Marvel in 1977, and back then, we’d work right off the original artwork, which was a real treat to see the original art of guys like Jack Kirby and John Romita [Sr.]. If books were really late though, we’d get a set of Xeroxes and then we’d attach a paper to the Xeroxes, letter it on the overlay paper, draw the balloon shapes around it, and they’d have somebody else paste it onto the artwork when it came back from the inker. When we did it that way, the letterer got $2 extra per page, but you didn’t get to work on the original artwork, which was really the biggest highlight for me, being an artist myself.

Jim Hoston, classical painter and colorist at Marvel Comics from 1993 to 1995: I was a colorist for just a few years at Marvel, and honestly, the job is a total blur. Basically, the inker, letterer and colorist were all working on pages at the same time, so sometimes I’d be coloring pages with the word balloons and sometimes without, depending upon how behind things were. Many times I’d have to do 22 pages over a weekend, which was a lot.

John Kalisz, colorist at Marvel Comics, 1992 to present: Things have changed a lot since Maximum Carnage. I’m still coloring comics now, and it’s almost a completely different process. Back then, they’d send me a Xerox of the original artwork shot down on heavier paper that would hold water colors. I would use Doc Martin’s dyes — which is what most people used back then — and paint them on. Then you’d have to write down the corresponding color code for the dye you put down. Those codes would then be used in the printing process to make sure the colors were accurate, so we were kind of the last step before the book went to print.

The Story

The first part of Maximum Carnage would hit newsstands and comic shops in May 1993 in the first issue of Spectacular Spider-Man. Much like Carnage’s debut the previous year, the book would prove to be a smash hit.

Toy Shiz: I remember collecting all the issues of Maximum Carnage when I was a kid. Carnage was just the coolest character back then. The biggest story highlight for me was in the very beginning, when Carnage breaks out of Ravencroft [Institute for the Criminally Insane], killing everyone before assembling his team of villains.

Forbeck: Once Carnage assembled his family of villains — like Shriek and Demogoblin and the others — they all became serial killers that were rampaging around New York City until Spider-Man assembled some friends to stop them.

Terry Kavanagh, co-founder of Inksmyth, Marvel Comics editor and writer, 1985 to 2001: There were so many great heroes that were assembled in that book. It’s always fun to use characters like Captain America, and I had previously written for Cloak and Dagger, so I was comfortable with them, but my favorite — as a fan — was Iron Fist. I was really excited to use that character.

DeMatteis: The basic idea of Maximum Carnage was to use the “grim and gritty” heroes and villains that were so fashionable back then and strike a contrast between them and the nobler good guys like Spidey and Captain America. The part with Cap in particular was a huge highlight for me, as I got to work with my brilliant Spectacular Spider-Man collaborator Sal Buscema. Sal and I hit it off pretty much from the first panel. My favorite sequence in the entire crossover is one I created just for Sal. In it, Spidey’s had the crap beat out of him and he’s crawling on the ground in Central Park. I mapped out a 12-panel grid as Spidey crawls closer and closer to the “camera.” Then, at the end of the page, he hears an off-panel voice that says, “How ‘bout a hand, son?” Then, after the page flip, we get an astonishing spread of Cap, reaching out to Spidey, offering his hand. “You look like you could use it.”

Those two pages captured the essence of both those characters — Spidey’s indefatigable spirit and Cap as the embodiment of hope — and Sal brought it alive as only he can. Those two pages alone were worth the whole crossover for me.

Kavanagh: There was a big moment for Spider-Man late in the story about him holding his ground about not using lethal force, which was a bone of contention between him and some of the other characters. While the story may be a bit more villain-centric than hero-centric, for Spider-Man, Maximum Carnage was more about him holding his ground, which is an arc.

DeMatteis: I don’t know if Maximum Carnage changed Spider-Man as a character, but the story underscored Peter’s commitment to compassion and simple human decency, standing firmly on the side of the light. That simple decency is, I think, Spider-Man’s greatest power.

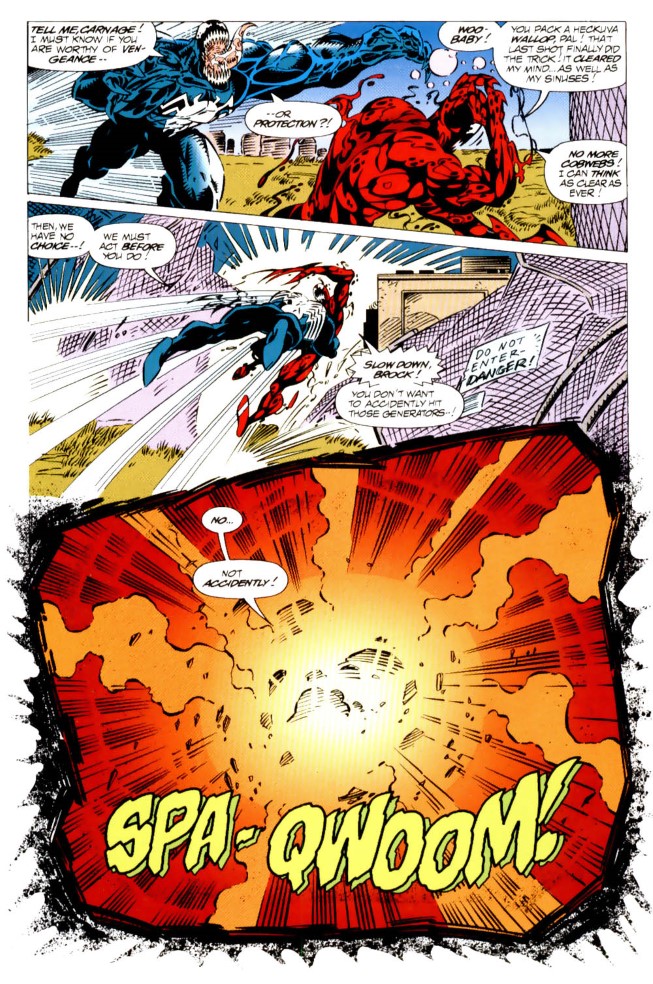

Toy Shiz: I loved Maximum Carnage, but I will say that it was a little bit anticlimactic at the end, unfortunately. They took down Carnage kind of easy-peasy. They just needed to blow Carnage up a little bit and it was over. Still, it was cool and it was just a wackadoo comic.

Beyond the Comic

While sales were good for Maximum Carnage, it wasn’t just a comic book story, as Marvel also created a number of other product tie-ins. Most notably, there was a 1994 video game from Acclaim Entertainment.

Fingeroth: The sales on Maximum Carnage were very good and the royalties were very good. The reviews were pretty good too, from what I can recall. It also spawned a video game, which ended up being huge. In retrospect, I think that’s what makes Maximum Carnage so memorable to people — it was that game.

Forbeck: I think Fingeroth is absolutely right. Without the game, Maximum Carnage just may have become another Spider-Man event that somebody reads and then they go off and do something else. But if you have a video game that brings it up over and over again, and if you spend hours if not weeks or months playing that game, that sticks with you and gets in your brain a little bit harder.

Mark Flitman, video game producer with Acclaim Entertainment, 1992 to 1994: Back then, we owned the entire Marvel license, which means we had everything and we always had a Marvel title out. We had just finished up the Spider-Man X-Men game and it was time to do the next title, so the VP of product development and myself went into Manhattan to Marvel headquarters and asked what they had coming up that we could do a game on. They started to tell us about a 14-part story coming out called Maximum Carnage, and as soon as we heard about it, we knew it would work. It had great heroes and great villains, and it was loaded with characters, so we knew this was it.

We started on the game while the comic was still being made, and it came out the following year, in 1994. Most games were based on a property more generally, but Maximum Carnage appealed to me because it was a whole story. I studied filmmaking in college, and I was very much into storylines. I felt that any game was better with a storyline. It also appealed to me because I grew up on comic books, and I wanted to bring the comic book panels to life in the game, which was very unique. So I got to bring panels to life directly from the comic, but with some movement included. It was a cool feature that I hadn’t seen before.

Being able to play as either Spider-Man or Venom was also a great feature because it offered an element of re-playability. Most games, when you finish them, they’re done, but if a game had a character choice or a choice of two different paths — which Maximum Carnage also had — it gave the player a desire to play the game again.

Toy Shiz: I didn’t have a gaming system when I was a kid, but I remember going to my friend’s house and playing Maximum Carnage. I remember that red cartridge and my friends talking about how cool that was. When I got a job as a teenager, one of the first games I went out and got was Maximum Carnage.

They also did a Maximum Carnage repack of some Toy Biz action figures, where they took figures of Spider-Man, Venom and Carnage that were already produced and repainted them and repackaged them with Maximum Carnage on it. They were just repaints of earlier Spider-Man figures, but they were still a pretty cool release.

Flitman: The marketing of the game was also a tremendous part of its success. One thing they did was give the game a red cartridge. I don’t know who thought of it, but in those days, you could do something that simple and it would have a huge impact.

Maximum Carnage also got a trailer that was released in movie theaters at the time, which is something that was never done before. They also sold a Maximum Carnage watch and some toys. They even did a special edition of the game for comic book stores that had exclusive pins and a hardcover of the 14-part comic.

DeFalco: I remember getting a copy of that game and giving it to my nephew. Later on he told me that he loved the game and he enjoyed the comic book too, but my nephew never read anything but The Punisher and Ghost Rider so I asked him, “What are you talking about?” He showed me that inside the game was a copy of the comic book and I remember looking at that and thinking, “Wait a minute! Somebody owes me money!”

Flitman: Back when I was making these games, I knew the numbers, so I knew if a game sold well, but it’s only been more recently that I’ve realized the impact the games have had on people. I’ve had people tell me that a game I made was “their whole summer” one year and that’s been very humbling for me. I think that’s why Maximum Carnage has stood the test of time so well — it captures a moment in their life.

James-Michael Roddy, creative director at Universal Studios, 1992 to 2010: Back in 2002, I was in charge of Halloween Horror Nights in Universal Studios: Islands of Adventure. Islands of Adventure had just opened, and we wanted to theme every island differently for Halloween. For the Marvel area, we thought, “What if all the villains took over?” The one we all gravitated toward was Carnage, so we made this maze as a training ground for villains with Carnage at the center. It was a great, memorable way to honor these amazing characters, especially Carnage.

The Legacy of ‘Maximum Carnage’

In the decades following Maximum Carnage, comics have changed a great deal, both in process and in style. But while Carnage still comes off as a character straight from the 1990s, he’s never left the pages of Spider-Man for too long. And now, with Venom: Let There Be Carnage coming out in the (hopefully) near-future, you can bet that Carnage will continue to wreak havoc throughout the Spider-Verse.

Saviuk: Maximum Carnage has been such a big deal. We do get certain residuals from reprint sales, and it seems like every couple of years they’re putting Maximum Carnage together in some other kind of volume and I’ll get a check in the mail. It’s kind of like the gift that keeps on giving.

David Michelinie, co-creator of Venom and Carnage, writer at Marvel Comics, 1978 to 1993: In the interest of full disclosure, I have to say that Maximum Carnage wasn’t my best comic book experience. I’ve never been a fan of “event programming.” As a reader, crossovers force you to buy bunches of comics you wouldn’t otherwise pick up, and as a writer, you end up being dependent on other writers to do their part, even if their styles, use of speech patterns and other focus points make characterization vary from chapter to chapter.

I wanted to write Peter Parker, Mary Jane and maybe a single villain in my stories to focus on those characters, but my issues of Maximum Carnage ended up as a lot of pages of people fighting each other — mostly for the fun of it — with the occasional character bit shoehorned in. As a result, I really haven’t gone out of my way to embrace memories of Maximum Carnage. I actually quit Amazing Spider-Man only eight issues later, so this wasn’t a happy time for me.

Fingeroth: Maximum Carnage was part of a movement in comics in the late 1980s and early 1990s where every comic had to be an “event,” so I think that may have backfired to a degree. That trend still continues today, where every story has to be a major, life-changing moment and everything is multi-part where you’re constantly trying to outdo yourself.

All these crossovers and big stories aren’t a bad thing, but I do think something was lost in that and there wasn’t as much room for smaller stories anymore, or stories that were just one good issue. That trend didn’t start with Maximum Carnage — I’d say maybe Death of Superman started it — but Maximum Carnage was another brick in that wall.

Wallace: It’s a pretty huge crossover, but it’s funny because if you look back at it now, it doesn’t seem like it’s as big as it was in the 1990s. You look at some of the characters, and it’s like, “Oh, who are these characters?” Like Demogoblin and Shriek — some of these characters aren’t A-list characters in Marvel or even in the Spider-Man mythology. The story was a product of its time, in part because the characters that are in there haven’t had the chance to really shine outside of Spider-Man, Carnage and Venom. But the story was really big back in 1993, it just seems a little curious now when you go back and refresh yourself on it.

I think part of the reason why it’s still so well-known is that those characters — Venom and Carnage — were so big back then that they’ll never totally go away. Plus, the title Maximum Carnage tells you so much, you really know what you’re getting. It’s one of those things where they just found the perfect title for it, which gave it this longevity, lasting longer than it would have if you called it The Symbiote Wars or something like that. Maximum Carnage is such a great title that many people got upset when the new Venom movie was announced, and it had a different name. It would be so much better if the movie would be named Venom: Maximum Carnage because it’s so much punchier than Venom: Let There Be Carnage.

Toy Shiz: When the Venom movie was released and they teased Carnage at the end with Woody Harrelson, all of that nostalgia and Maximum Carnage stuff just came flooding back. The 1990s will be making a glorious comeback whenever that sequel comes out.

DeMatteis: Like almost every crossover, Maximum Carnage probably went on too long and had too many characters and too many colliding points of view. And I recall that some folks felt that, in trying to take a stand against the ultra-violent characters of the day, the story indulged in too much of that violence — and they may be right. But Maximum Carnage clearly struck a nerve with readers. It’s had a long, healthy life and doesn’t seem to show signs of stopping. So perhaps the underlying message — that compassion and simple human decency will win out in the end — is why the story has lasted.

Fingeroth: As far as legacy goes, I guess you could say I’m surprised that any story we do might still be talked about and argued about some 30 years later. Back then, we were just a bunch of guys trying to do our jobs while trying to appeal to the widest fanbase. If anything, the legacy goes back to Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, as well as guys like Larry Lieber and John Romita. What those people created was so powerful and monumental that it would last 30 years into the 1990s, then another 30 years until today. As wonderful and talented as we all were on Maximum Carnage, so much of it goes back to those initial ideas and characters that those guys created.