Growing up, Nico Meyering, now a 31-year-old living in Philadelphia, had nothing in common with his younger sister, seven years his junior. She was outgoing, while he was more introverted. She was into sports; he wrote for the school newspaper. “We didn’t really have a lot to bond over,” Meyering tells me.

One morning, however, they found common ground: a love for Digimon.

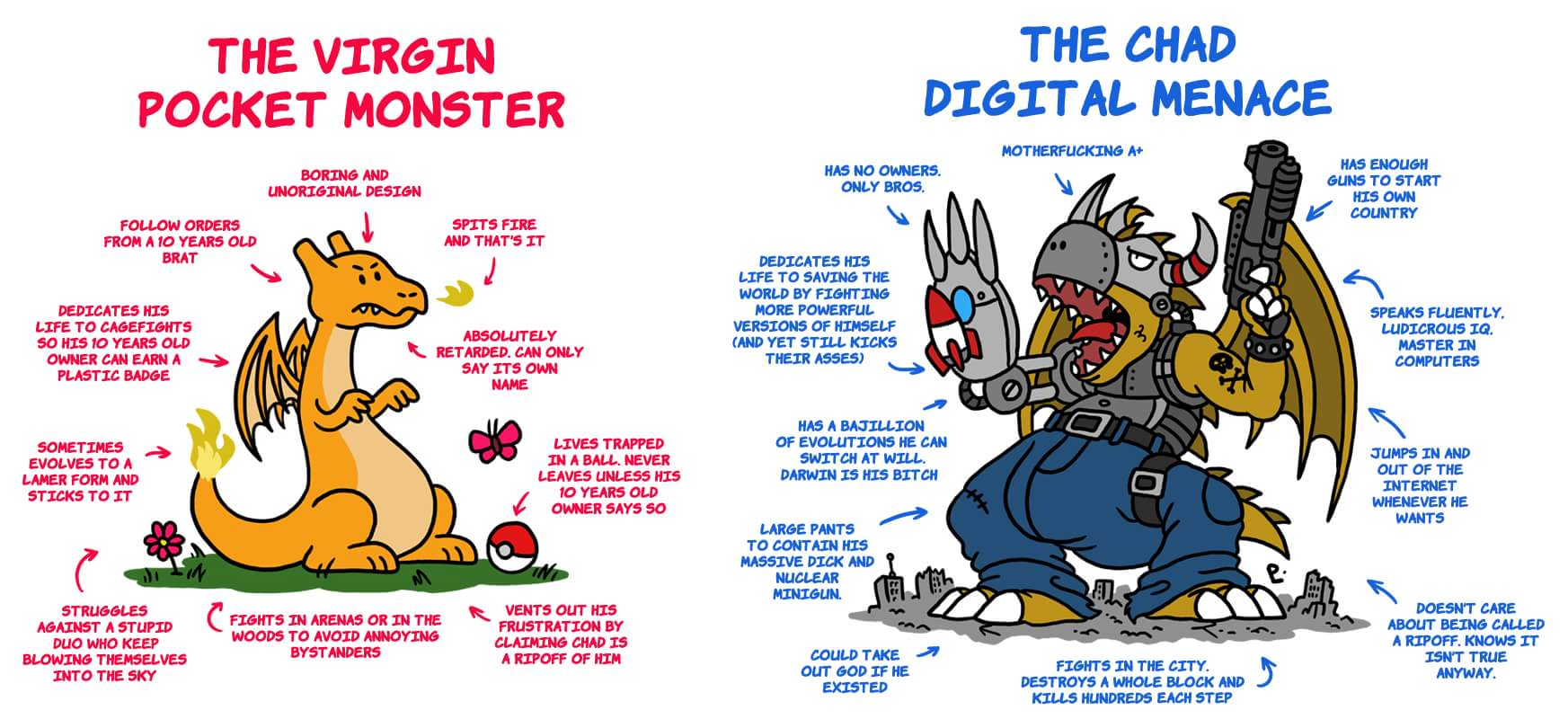

For the uninitiated, Digimon: Digital Monsters was a Saturday morning cartoon — some might call it technically anime — that ran parallel to Pokémon. Diehard fans preached the distinctive merits of each show, but for American kids growing up in the ’90s, the premises were similar enough: kids with monster-animal companions fight other kids with monster-animal companions.

But Digimon never stood a chance. By the time Digimon: Digital Monsters came out, in 1999, the Pokémon Company had already released its Pokémon Red and Blue games for the Nintendo Game Boy, now one of the best selling role-playing games of all time. Today, Pokémon is the highest grossing video game franchise, beating Mario by about $60 billion, and it’s not slowing down. A new Pokémon movie or game seems to come out every minute, and the fandom — old and new — continues to grow. This month, Detective Pikachu, starring Ryan Reynolds, hit theaters. A couple of Pokémon-centric games for the Nintendo Switch were released this year, and we also got the announcement of upcoming Sword and Shield games, which are throwbacks to Red and Blue — the games that sparked a movement in the U.S.

As for Digimon fans, they’re left with little but their memories. Meyering thinks fondly of the days he’d bond with his sister, who back then was the only person in his life who loved Digimon too. Meyering first hooked his little sister by showing her 2000’s Digimon: The Movie. “Since we couldn’t find common ground on nine out of 10 things, talking Digimon and playing the [Playstation game] Digimon Rumble Arena with her meant a lot to me,” he says today.

When his sister moved away, Meyering felt alone again in an endless sea of Pokémon diehards. He idled along as his preferred series faded away, while Pokémon and its bottomless coffers molded generation after generation into a loyal Pokémon army.

MFW I realised that people are slowly forgetting about Digimon in this day and age from digimon

So what’s it like to be the last of a dying breed? I talked to a few more Digimon die-hards about being a dedicated fan of a franchise that’s quickly fading from the public sphere — as its rival title continues world domination.

‘Kids Can Be Really Mean When They Decide to Start Hating’

Digimon fans are used to being in the minority. In my experience, there weren’t many Digimon fans on the playground, to say the least. Pokémon not only had the TV show, but it had the collectible cards and the smash-hit Red and Blue Nintendo games. Where I grew up, in the late ’90s and early 2000s, everyone was a Pokémon fan, and if you weren’t, you were different. And on the playground, different is bad.

Ryan, 20, fell in love with Digimon because of the friendships formed between humans and their monsters. Digimon weren’t just the kids’ pets — they were friends. The humans and monsters worried about each other, confided in each other.

At first, Ryan wasn’t shy about his Digimon fandom. He’d design new monsters in a sketchbook, and even “model a Digivice using polymer clay and run around the woods pretending to be a Tamer or a DigiDestined,” he explains.

As a result, he was often bullied into spending recess alone, he says. “Kids can be really mean when they decide to start hating on something you like, so the few times I was able to share my drawings and stuff, I often got beat down and teased.”

Even the kids who might’ve empathized with him were Pokémon fans, not Digimon fans. And so Ryan would hide during recess with his drawings, relying on his imagination to keep him company.

‘Pokémon Is Basically Cute Dogfighting’

Nigel Saskrotch (a pseudonym) was 14 when Digimon first aired, in 1999. He remembers watching it after high school because its time slot on Saturday morning was too early. “I knew I was too old for [the show], but I loved it anyway,” he tells MEL.

“What I loved about it was that it was a show about friendship and personal growth,” Saskrotch says. “Pokémon was always extremely episodic to me. They’re on their way to a tournament, a new Pokémon gets discovered, Team Rocket tries to catch it (I think?), Team Rocket loses, they continue on to the tournament. Next episode.”

“But on Digimon, these kids were lost. They became spiritually linked to their Digimon, who then tried to help them find a way home. They fought for survival, whereas on Pokémon, they were just amassing as many of these wild animals as they could to make them fight. It’s basically cute dogfighting.”

On Reddit, the Digimon Fandom Embraces Thirtysomething Life Together

Dan, a 28-year-old in Canada, also raved about Digimon’s depth and sensitivity. It “felt more mature, with real risks; as a kid I didn’t know if they were going to make it through,” he says.

“I’m always trying to get people to watch the third season of Digimon,” Saskrotch says. “[Because] even though they’re really trying to sell people on the card game through a lot of it, that season gets super-emotional and dark. One girl gets so traumatized she stops speaking for a couple episodes.”

In Digimon, Ryan adds, “each kid has their own troubles, doubts and fears to go along with those aspirations, dreams and ideologies. Their Digimon learn and grow with them, helping them develop as people who can resolve their own problems and flaws.”

Digimon “made me have more feelings,” Meyering explains. “I’ve always been introspective; I’ve always searched for in-depth meaning in any movie/show/game/book that I consume. Digimon dealt with those things. … You don’t get that with Pokémon, you don’t get that with [Dragon Ball Z],” he adds. “In Pokémon you have just Ash wandering around the world over and over and over.”

How Pokémon Achieved World Domination

Why did the Digimon franchise struggle to find success beyond the TV show? Meyering explains: “Pokémon succeeded because it had a very good game on a system you could take with you, whereas Digimon only had the Digimon World games, if the whole Tamagotchi-style thing didn’t appeal to you. In [Digimon World] games, you had to raise your Digimon not only through fights but also through other mechanics, and I think that was a hard sell.”

But also, Ryan adds, Digimon struggled because multiple publishers juggled the series. “Its American releases were often plagued by large companies trying to make the fastest and biggest buck off of it that they could,” he says.

Also, Meyering explains, Pokémon was easier to digest for kids, thanks to the show’s “linear nature — one storyline, one set of characters in the TV show. Whereas as an adult, I now appreciate the variety and complexity of Digimon.”

In Pokémon shows and movies, Meyering argues, “a human tries to catch and train as many Pokémon as they can. It’s quantity over quality.” It’s this simplicity that makes sense to kids and fueled Pokémon’s popularity. “As kids, you want to be popular, and you measure that popularity by how many friends you have, how many people like you.”

Someone posted this on Twitter and the Pokémon fans were salty ? from digimon

“Digimon isn’t as popular as Pokémon and that’s okay,” Meyering says. It just makes the remaining Digimon diehards a tighter-knit community. In their hearts, Digimon is the superior series.

And now, as grown adults, the Digimon fandom seems to be growing older and smaller. It’s no coincidence every person I’ve talked to is near or in their 30s. Digimon fans in the subreddit r/Digimon talk about raising their kids as fans and how people react to their Digimon tattoos.

So found a vhs of digimon the movie an he’s loving it! Proud dad ? from digimon

“Being around Pokémon fans basically everywhere is just something I’ve come to terms with,” Saskrotch says. “I’m part of the Chiptune scene, 70 percent of which is based around writing music with Game Boys. … I’ve only met a couple people in the scene that are into Digimon, and most of them still prefer Pokémon.”

How it feels listening to a pokemon fans reasons why its supposedly superior to digimon from digimon

“I often just feel disappointed that Digimon doesn’t get the recognition that Pokémon does in the world at large,” Ryan says. “Even as I’m writing this email right now, ‘Pokémon’ is recognized by the spell check as a properly spelled word, but ‘Digimon’ is somehow incorrect.”

And if Pokémon diehards do recognize their fandom, it’s mostly to charge Digimon fans as being contrarian or needlessly nostalgic. On Twitch, Saskrotch says, another “streamer insinuated I only preferred Digimon as an attempt to make myself ‘appear to be a free-thinking individual.’”

Wonder if roommate will notice addition to his pokemon (and some Nintendo) shrine. from digimon

Ryan says he’ll bring up Digimon with a new group of people and get eye rolls. “It makes me feel like I’ve been doing something wrong or been a part of some weird part of culture that they rather have go unmentioned,” he says. “[People] react like they just saw their grandmother dab in front of all their friends, so I usually never bring it up. Even at work or in certain friend circles it just gets dismissed as ‘another Pokémon clone’ — suddenly making me feel like I was wrong to even mention it.”

Meyering says he still advocates for Digimon, but keeps it “low key.”

“I’ll post about it on Facebook, Twitter and Reddit, I’d bring my fiancée to see some parts of [the movie Digimon Adventure tri]. I tried to get my friends to go, but that was no sell.”

That said, when Meyering went to a screening of a Digimon movie in Albany, New York, he was surprised by the number of hardcore fans there.

Digimon 8 original crests. Repost, touch up done, healing finally done. from digimon

“I wasn’t expecting to see many people there,” he explains. “What’s more, people of any and all ages would bring their Digimon stuffed animals with them! The Digimon community is so welcoming and so wholesome, and for someone who didn’t grow up with other fans of the series, it was incredibly moving to me.”

The Surviving Fandom

Beyond the hot-takery you’d expect to find on the internet, there is a small (compared to Pokémon fandom, at least) but tight-knit community both online and at Comic-Cons.

Unpopular opinion: Digimon is better than Pokemon.

— Natasha Ward (@Otakuish115) April 30, 2019

“There’s a huge nostalgia factor powering Digimon,” Meyering explains. “Cosplay at cons, stuffed animals, blind boxes, keychains.” He adds that the fandom has some “excellent fan forums, like With the Will, and of course we have the subreddit, which is super-inclusive and positive.”

We really need more Digimon-themed memes, so I decided to make one. Feel free to use it! from digimon

“But,” Meyering says, “nostalgia isn’t going to keep us going forever. We need new fans, and that probably means younger fans. A lot of us are older fans who remember the first few seasons of Digimon. I think the best thing for Digimon as a franchise right now is different media for different audiences: a new TV show for the kids, new video games for the teens and adults.”

Meyering and his sister aren’t as close as they used to be, but thanks to the Digimon fandom, he’s found his people. Later this month, Meyering will be giving a “Digimon 101” presentation at Thy Geekdom Con, a comic convention in Oaks, Pennsylvania. “It’s about why Digimon is still relevant so many years later,” he tells MEL. “What I like about Digimon is that it shows all of the characters, both male and female, growing and maturing. They become their best selves when they focus on their best qualities.

“It was an important message for me back then as it is for adults now,” he concludes. “Our emotions are what make us human; emotions are a source of strength and pride rather than shame. Digimon has always been about letting our best qualities define us, and about caring for our friends.”