“I remember going to Chuck E. Cheese’s as a kid a lot. The animatronic band would take a ‘break between sets,’ the characters seemed like they shut down and the lights would dim on stage. But they never stopped moving completely. Every few seconds one would make a slight movement of the head, eyes or limbs. It scared the shit out me as a kid! Because I knew they were robots but the fact that they would ‘fidget’ after being still for so long made them seem alive. So creepy.”

— SilverBell2449, Reddit

In 2017, CBS News announced that “Chuck E. Cheese’s animatronics may take a final bow.” In an interview with CEC Entertainment CEO Tom Leverton, the company announced that, as part of a new concept for the restaurant, the animatronics would be phased out over the next several years, being replaced with a dance party hosted by a person dressed as Chuck E. Cheese instead.

Leverton explained that “the kids stopped looking at the animatronics years and years ago, and they would wait for the live Chuck E. to come out,” and that “the animatronics became a sideshow.” While some parents — particularly those whose children find the glitchy bots terrifying — may welcome the news, others who grew up with the robotic Chuck E. and his accompanying band see it as the sad passing of an icon. But where did this icon come from?

Grab a slice and let’s find out.

Chuck E.’s Humble, Mousey Origins

On May 17, 1977, the first Chuck E. Cheese restaurant — then called Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatre — opened in San Jose, California. The brainchild of Atari founder Nolan Bushnell and marketing whiz Gene Landrum, the restaurant introduced a new experience to families, which included an arcade along with a pizza restaurant. From the start, the innovation was a massive success and Chuck E. Cheese began to grow almost overnight. While its two founders offer up a storied — and occasionally contradictory — tale about the restaurant’s early days, one thing is clear: the animatronics weren’t the primary focus in the early days of the establishment, and they offered little foresight into what they’d later become.

Nolan Bushnell, co-founder of Chuck E. Cheese and Atari: At the time, Atari was selling coin-op games for $1,500 to $2,000, and during their lifetime, they’d earn $30,000 to $50,000. I felt that I wanted to be on that side of the equation as well, but I didn’t want to compete with the people I was selling games to who were already in the existing locations. I had two goals — to create a big, freestanding arcade, and to have a place that was kid-friendly. We knew kids wanted to play the games, but they had no place to do that, as bars weren’t possible and arcades were teenage hangouts.

I decided pizza was the right food because it had a delay time that would allow for gameplay. Back then, the most successful pizza parlor in the Bay Area was Pizza and Pipes, which had a deconstructed Wurlitzer theater organ. It was extremely successful when they had an organist, but it was quiet when there was no organist, so I wanted entertainment that didn’t involve labor. When I took my kids to Disneyland and saw the Tiki Room, I felt that that could be the solution — a mechanical, computer-operated entertainment system. Once I had the plan sketched out, I talked to Gene Landrum, who was in my marketing department at Atari. I felt that he was capable and could spearhead the project. Gene then oversaw the entire project and did a great job.

Bushnell, excerpt from Fast Company interview: We could really say, in some ways, that Gene was the founder of Chuck E. Cheese, because he was the guy I hired to bring Chuck E. Cheese into fruition. He was the guy that found the pizza recipes, he rented the facility and he hired the first people. He was very, very instrumental.

Gene Landrum, Chuck E. Cheese co-founder: Bushnell gave me the money and he gets so much of the credit, but let me tell you how it happened. May 17th, 1977, I opened the first Chuck E. Cheese in San Jose, California and when I was putting it together, I went to Disneyland to do some research — I’m a bit of a research nut, see, so I went to Disney. They had hundreds of games and you could also go to the park and see all these animatronics, like the Country Bear Jamboree, and of course, they had Mickey Mouse! So I said to myself, “I got it! They have Mickey Mouse, I can do Chuck E. Cheese, it’s sounds the same, see? Mick-ey-Mouse, Chuck-E.-Cheese.” So that’s where I got it from. And Nolan had a rat costume in his office, so it worked out.

I wanted to create a place where a kid could be a kid. So often when you take a kid to a restaurant the parents say, “Sit there, be quiet,” and the kid knows that this isn’t a place for them. So with Chuck E. Cheese Pizza Time Theatre, I wanted to create a place where a kid could be a kid, so that’s where that came from.

Back then, a pizza parlor in America was doing about $250,000 to $300,000 of revenue each year — that was the max revenue — and that’s what they did in these little pizza stores with this small square footage. My first store was 5,000 square feet, and I was doing $1.3 million. I was doing a million bucks more than everyone else, and the reason for that was because families were coming. Because the parents worked all week, on weekends, they wanted to take the kid where the kid wanted to go, and that was Chuck E. Cheese. We did so well that we soon started to open more and more of them.

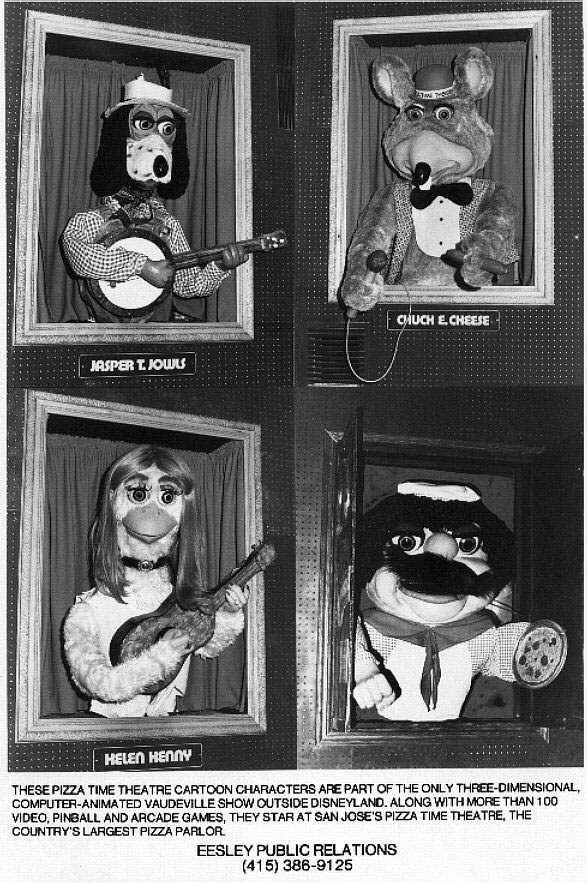

Travis Schaffer, superfan and founder of ShowbizPizza.com: In those original two restaurants, the animatronics were framed portraits that hung on the walls of Pizza Time Theatre. They were done by a guy named Harold Goldbrandsen, and he wasn’t even an animatronics guy, he was a costume builder, so the robots were very simplistic and not the central focus.

Once they got away from doing the portrait figures, they started mass-producing steel frames and created the characters out of wood, foam and cloth, along with the mechanics. These were basically the same simple robot built over and over again, and they’d be stamped out and redressed for each character. They were called the “Ottoman” robots because it was basically like reupholstering an ottoman, but they served their purpose.

Meet the Bots

Over the past 40 years, many characters — e.g., Dolli Dimples, Madame Oink and Crusty the Cat — would come and go on the Chuck E. Cheese stage. But a core five would stand the test of time, lasting even to today in those restaurants that have yet to be overhauled by Chuck E. Cheese’s changing image.

Duncan Brannan, voice of Chuck E. Cheese, 1993-2012: Chuck E. Cheese is a really genuine slice of Americana because, what other figure out there is instantly synonymous with a birthday? Chuck E. Cheese is the birthday guy, and he’s peerless in that way. He’s all about the magic of a birthday and the magic of a show and all the things that make a kid’s world special. Chuck E. was just the lead singer of the band, though. It was Munch’s Make Believe Band — Chuck E. was just the guy to come along and say, “Hey, I think we can take this somewhere…”

Brannan, voice of Munch, 1993-1998: Originally, Munch was basically the pizza version of Cookie Monster. Over time, though, he changed and became the keyboardist and the bass [vocalist] of the group, as well as the bandleader. He’s also this kind of tender character as well. Yeah, he likes to eat, but he’s also the big Teddy bear of the group — one of those guys who really never seems to have a bad day.

Bob West, voice of Pasqually, 1986-1999: Pasqually is pretty much the chief pizza chef for Chuck E. Cheese. He’s the guy who comes up with all the recipes and he does all that behind-the-scenes work in the kitchen, but he’s also a huge fan of opera and of singing in general. He also tells a lot of good, corny jokes. He’s a very jolly fellow.

West, voice of Jasper T. Jowls, 1986-1998: Jasper is basically your flea-scratching country dog. He plays the banjo, and he’s a pretty mellow dog who likes to sit on the front porch with his friends. He’s very friendly, warm and jocular.

Showbiz Pizza Wiki excerpt: Helen Henny is a vocalist (formerly tambourine player) and bassist of Munch’s Make Believe Band at Chuck E. Cheese’s. Eventually, Helen [became] the second most seen character on merchandise, behind Chuck E. himself. She [has] a sweet and cheerful personality.

Showbiz Pizza, the Rockafire Explosion and the 1980s Pizza Wars

With the success of Chuck E. Cheese, it was inevitable that it would eventually face competition from imitators. Enter Showbiz Pizza, a pizzeria/arcade with the same concept, but with animatronics that were far more advanced. On March 3, 1980, the first Showbiz opened, and many more locations would soon follow.

At the same time, Chuck E. Cheese was franchising all over the country: Many of these new locations would soon be rivaled by a nearby Showbiz Pizza, which would inevitably hurt Chuck E. Cheese’s in large part because Showbiz’s animatronics — a band called the Rockafire Explosion — proved to be a major draw. While Landrum had departed the company by this time to pursue other ventures, the “pizza wars” of the 1980s would soon get into full swing. Before all that though, the origins of Showbiz Pizza can, weirdly enough, be traced back to a deal to create more Chuck E. Cheese restaurants.

Schaffer: The history between Chuck E. Cheese and Showbiz Pizza is super complicated. Basically, Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatre started under Atari, but they really didn’t want anything to do with it because they were a video game company and they had no interest in this arcade with a rat in it. But they agreed to let Nolan make one of them. When Nolan ended up quitting Atari, he bought the concept from Atari.

Once Nolan owned it, he wanted to start franchising. So they had this big co-development agreement going with Holiday Inn, but the whole thing fell apart. Yet, because Nolan was still friends with one of the guys who was working with Holiday Inn, it was suggested to him that he reach out to Bob Brock, the largest franchisee of Holiday Inns. And so he pitched it to Brock, and Brock was all about it — they signed this massive co-development agreement that called for 280 Pizza Time Theatres to be built throughout the Midwest. That all lasted for less than a year, when Brock broke ranks with Bushnell and Pizza Time Theatre after meeting an inventor named Aaron Fechter.

Aaron Fechter, creator of the Rockafire Explosion: I met Bob Brock at the end of 1979, and at that time, he’d already signed a deal with Nolan Bushnell to build 280 Pizza Time Theatres. I’d previously met Nolan Bushnell in 1977 and 1978, and he’d wanted me to sell him my animatronics for his Pizza Time Theatres. But I didn’t trust him — I figured he’d just buy one character from me, get it to California, then reverse engineer it and start copying it so he’d never buy another character from me. So I refused.

Although Bushnell knew about me, when he signed the deal with Brock in the summer of 1979, he told Brock that he was the only person making animatronics outside of Disney. Brock signed on because Brock knew the animatronics were the key to the Pizza Time Theatre concept — he was the biggest franchisee of Holiday Inns, so he knew how to run a restaurant, he knew how to run a game room. It was obvious he needed the animatronics.

So when I read about this deal between Brock and Bushnell, I said to myself, “He should be signing a deal with me!” I knew Brock would be at this trade exhibition at the end of 1979, so I set out to really wow him with two new shows of the Wolf Pack Five, which I’d debuted at the trade show back in 1978 and everyone went crazy over.

I went into that trade show with the intention of attracting Bob Brock, but when I got there, I forgot all about it. We were so busy and so successful that I didn’t even think about Brock. But when I got home, there was a call waiting for me — it was from Bob Brock! He said that he’d sent his men to the show, and he was pissed to learn that I existed and that Bushnell didn’t tell him. So we met, and I told him about my history with Bushnell — Bob decided to get out of the deal with Bushnell on the basis of fraud and go into business with me [instead].

I got a 20-percent stake in the company, and we created Showbiz Pizza, starring the greatest animatronic band that ever existed, the Rockafire Explosion.

“I remember being fascinated studying the ones at Showbiz. Like part of me was freaked out about them becoming sentient, but I also wanted to know exactly how they worked.”

— juel1979, Reddit

Fechter: The Rockafire Explosion are animatronics operated by pneumatics. Pneumatics can be used for robots or animatronics; it simply means to move things using air pressure. The difference between robotics and animatronics is that, generally, robotics are a machine that perform some work, whereas animatronics are for entertainment. It’s like a mechanized puppet show.

In my opinion, animatronics are best controlled by pneumatics because the characters can be lighter, as they don’t need all the motors in them and their movements look better — more lifelike — with pneumatics.

Everything was great for the first few years. I went from like, 30 employees at my company to about 300, because Brock wanted to build all those 280 restaurants still. It was just balls to the wall all the time, so I trusted the executives at Showbiz Pizza to run the company while my company — Creative Engineering — built the shows. It was all separate, so I didn’t tell them that they were growing too fast or anything like that, but I did believe it — I did feel it.

Schaffer: At Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatre, since Brock dropped out, they were hurrying to add franchises all over. They only had a handful by 1980 — about six to ten restaurants — so to suddenly expand like that was a big undertaking. Harold Goldbrandsen told me that they wouldn’t even consider a mom-and-pop operation that only wanted to open one franchise — they only wanted big money people who could open several stores.

Fechter: it was like a gold rush. We had to beat Chuck E. Cheese to the best locations, so the executives of Showbiz Pizza were growing so fast their heads were spinning and they were spending money way too fast. They were out of money before they even knew it, and by 1983, they decided not to build anymore restaurants. But it was already too late.

Additionally, during all this, Bushnell decided to sue Bob Brock, and Bob Brock decided to countersue. Brock held a mock trial, but he lost his own mock trial and decided that, instead of going to trial, he’d settle for $5 million per year, which was ridiculous! By the way, that $5 million was the only money Bushnell was making, because he was even worse off then we were. We were both on the ropes in 1983. It was really bad, and even with that $5 million, Bushnell still went out of business before we did.

The New York Times, March 29, 1984, excerpt: Pizza Time Theater Inc., a six- year-old specialty-restaurant company based in Sunnyvale, Calif., announced yesterday that it had filed for reorganization under Chapter 11 of the Federal bankruptcy laws.

Henry C. Montgomery, 48 years old, who was appointed this week as president and chief executive, described the move as the only possible alternative for survival of the company, which operates and franchises a chain of about 270 restaurants under the name ”Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theater.” The units feature coin-operated games and musical entertainment by computer-controlled robot characters. Forced Liquidation Feared.

Fechter: After a while, Showbiz Pizza had to do whatever we could to stay afloat, so we had to bring in money people — vultures — and they wanted to control Showbiz Pizza, control me and control Bob Brock, so I began using my percentage to veto bad idea after bad idea. Then they had the worst idea of all — to merge with Chuck E. Cheese.

We were fighting Chuck E. Cheese for five years, and we knew we were better than Chuck E. Cheese. They were crap, and we were great, that’s what we believed. We were rivals. We don’t want to buy them out, we want to kill them! If they’re going to go out of business, let them go out of business. Don’t prop them up. Kill the rat! Let me plunge the sword through Chuck E. Cheese’s heart!

The Washington Post, July 15, 1985, excerpt from “Chuck E. Cheese Gets New Lease on Life”: After going bankrupt in March 1984, the parent company was bought by Texas-based Brock Hotel Corp., which created the new company, Showbiz/Pizza Time Theater Inc. There are now 350 restaurants with family entertainment and pizza since the Chuck E. Cheese restaurants merged with ShowBiz Pizza, a similar restaurant chain.

Schaffer: By this time, things had gotten so bad between Aaron [Fechter] and ShowBiz Entertainment that they were using a lawyer as a go-between for the two of them. The people who were running Showbiz at the time wanted the intellectual property for the Rockafire Explosion — which Aaron still owned — but he refused, and they basically said, “Fine, we’ve got another plan in place.”

By the mid-to-late 1980s Aaron was gone, as was Bob Brock, as he sold his shares. Bushnell had left already sometime around when Chuck E. Cheese declared bankruptcy. They eventually decided to bring everything under the same umbrella and stop using Aaron’s characters because they didn’t own them, so they began something called “concept unification.” Because it would have been too expensive to rip out and replace all the Rockafire Explosion characters, they decided to retrofit them with new cosmetics — they became the Chuck E. Cheese characters, and that’s where Munch’s Make Believe Band came from.

Chuck E. Cheese, 1990s to Today

Following concept unification, all the restaurants would eventually be renamed Chuck E. Cheese Pizza and eventually just Chuck E. Cheese’s. But despite that uniformity and the elimination of the Rockafire Explosion characters, vastly different experiences could be found at various Chuck E. Cheese restaurants, depending upon the history of each particular location.

Schaffer: Even to this day — for the restaurants that still have animation — you can go to a restaurant in one part of town and then drive to another one 10 minutes away and see something completely different. In some you’ll find what they call an “existing stage,” which is what they call the one from the older Pizza Time Theatre. Not the picture frames, mind you, but the simpler Chuck E. Cheese “Ottoman” robots. They look like the retrofitted Showbiz bots but they’re not — they don’t move as much and they aren’t as complex. Then there are the retrofitted Showbiz Pizza ones, and there’s another called Studio C, which is a brand new bot of just Chuck E. that they came out with around 1997.

Brannan: Eventually, I was also programming the pneumatic shows [as well as voicing Chuck E. and Munch]. I had a lot of fun with that and I got really, really good at it. That was a blast. Back then, it was all running on VHS and timecode, so basically, we’d sit there at this little programming desk with all these buttons on it. Those buttons would send the air through the tubes in the characters and you’d sync the movements to the music. It’s a pretty simple operation when you look at it now, but back then, it was high tech. Anyway, we’d create the show at the corporate office in Dallas and send the files to all the restaurants.

I actually figured out a way to get more pop and response out of the characters to make their emotions more fluid, by pulsing the air through them in different ways. And so, when the next show came out, all of the techs in the field were going, “Dude, what did you guys do? Our characters are moving differently. It’s more lifelike!” But one of the things that eventually happened was — because I was moving more air through these tubes and because techs in the field weren’t taking as good of care of their robots — things started breaking more frequently. Eventually our programmer put a data limiter on them so that no one could do that anymore. I think they actually called it a “Duncan Meter,” because it was made specifically for me so that I couldn’t put as much data into the show.

Chuck E. Cheese’s Creepy Legacy

With deteriorating animatronics and no central concept, Chuck E. Cheese’s house band has taken on a unique legacy. As the remaining bots break down further, the more frightening they’ve become. Because of this, the band has freaked out adults, terrified children and has served as the inspiration for the popular horror game Five Nights at Freddy’s.

Fechter: You know, it’s funny, they can’t help but be creepy. To start with — when it’s brand new and perfect — it’s kinda creepy because it’s so good. You look at it and you know it’s not real, but you’re willing to forego your disbelief and enjoy the show. That’s what I tried to do: I tried to produce a show where you watch it and relax and you just go ahead and believe that these characters are real. And that’s creepy because all of a sudden you go, “I got fooled by robots.”

As they get older, they do the same thing as humans. When you’re born, you’re cute as hell, but as you get older, you just get creepier and creepier. With animatronics, it’s no different. They’re going to get creepier and creepier if you’re not keeping up with it. So if you go to a place like Billy Bob’s Wonderland where they’ve still got their show — man, I don’t know how they do it, but they got the creepiest show I’ve ever seen.

Things are falling apart and they let it rot anyway. The eyeballs are completely turned around in the head, the arms are hanging off. They wrapped duct tape around Billy Bob’s hand to keep it from falling off, and the duct tape is coming loose. The faces are so creepy it’s almost become art, you know?

“As someone who works at a Chuck E. Cheese, I can tell you, even when we turn the shows off, they still move, and dear god, they’re freaky when we have to clean them. I never understood why people would want them at a kids place.”

— Bobbob253, Reddit

Brannan: When you’re talking about a 6-foot rat walking around a restaurant, that’s creepy even for a New Yorker, but imagine it from a little kid’s perspective!

As for the animatronics, long before I became Chuck E., I used to work for a Showbiz Pizza in the game room. I was there at closing time cleaning things up — I was the guy who had to polish the bots and make sure everything was spit-spot for the next day. I can tell you firsthand, when you shut down the lights, there’s a room full of bots that are just staring off into the netherworld with those giant, cue-ball-sized eyes with the pupils always dilated. It is kind of creepy.

The Rebirth of the Rockafire Explosion

While terror drives one area of the Chuck E. Cheese fandom, another feeling that’s evoked is pure nostalgia — particularly when it comes to the Rockafire Explosion, as Billy Bob, Fats and the rest have been reborn online by fans who fondly remember the band from their childhood. It’s become the subject of a documentary, and they’ve been featured in music videos, including one by CeeLo. Most significantly, though, fans like Travis Schaffer convene online on the Chuck E. Cheese and Showbiz Pizza fan sites and wikis to remember the heyday of their favorite animatronics.

Fechter: All of a sudden, with the internet, something new was happening and fans from the 1980s were finding me. They’d grown up and were in their 20s — they had jobs, families and children, and they were telling me what I always wanted to hear: “Aaron, your show was so much better than Chuck E. Cheese.” I didn’t hear that until the internet came along because there was no way for anybody to tell me. All of a sudden, the kids who were cheated out of the Rockafire Explosion by Chuck E. Cheese were writing me and telling me that they loved my show. I was loving it!

Schaffer: I started showbizpizza.com back in 1999, so we’re coming up on 20 years. When I started the website, there was nothing on the internet that I could find in relation to Showbiz Pizza Place. So I was like, well, I guess someone should make a website. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I went ahead and started it anyway. And eventually, all these other fans found it.

Rockafire, and the sophistication that Creative Engineering put into it — I mean, I love that show. That’s what I grew up with. I was fascinated with it when I was a kid. So much so that I’d go home and write stories about them. I bugged my parents to death about them. They sold records so I could listen to their songs at home even though we couldn’t always afford to go to Showbiz. It just kind of lives with me all the time, to the point where now, the whole basement of my house is going to be my own private Showbiz museum, complete with a Rockafire Explosion band that I bought from Aaron in 2005 and the Chuck E. Cheese and Crusty the Cat portraits from the first Chuck E. Cheese restaurant. Then I’ve just got 20 years’ worth of dolls and records and tokens — thousands of items.

Chuck E. Cheese, the Birthday Guy

At the same time, Chuck E. Cheese and his supporting cast have yet another aspect to their legacy. Chuck E. Cheese is still “the birthday guy,” as Duncan Brannan puts it, and even with the animatronics enjoying their current farewell tour, they’re still making memories.

A Representative from CEC Entertainment: Our animatronics are certainly legendary, and they bring up fond childhood memories for millions of adults and fans across the country. As we move forward, we believe our live Chuck E. experience provides the best entertainment value for kids, who have higher expectations of realism and special effects. This hourly interactive experience, in which Chuck E. dances and poses for photos with the children, has become the iconic experience for kids today, now strengthened with a new light-up dance floor and contemporary music. Animatronics aside, we believe in the value of our characters and they will continue to be an essential part of our brand as we move forward.

Brannan: Nolan Bushnell and those guys back then, it was genius, just pure genius. It was so cool because we had watched cartoons for years, but to be able to go somewhere, sit down and have a meal and a game room over there — that already was cool. But then you could go over here and watch these robots do a show! It was outrageous, and it’s created such a magical experience for so many families.

“They’re still creepy as shit.”

— musselshirt67, Reddit