The last time we saw Wilson in ultimate social-distancing movie Cast Away, things weren’t going so well for him. After being best buds with Tom Hanks for four years on a small island in the South Pacific, Hanks and his trusty volleyball set sail upon a makeshift raft, determined to be rescued by a passing ship in the ocean. But after a storm, Hanks finds his spherical pal adrift, having come dislodged from the post he’d been tied to. Hanks tries to rescue him, but Wilson is too far gone.

After screaming “I’m sorry Wilson!!!” as his buddy drifts away, Hanks gets rescued by a passing ship, flies back to America and sets out for a life of new possibilities. But what of Wilson? Since director Robert Zemeckis never revealed what became of the movie’s second biggest star, it’s been left to me to explore the possibilities.

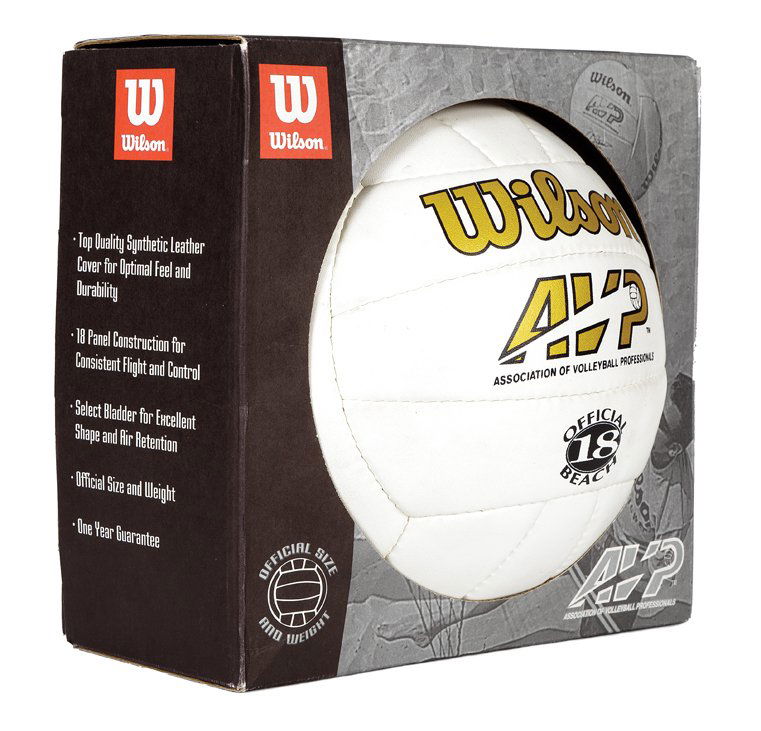

The first thing I had to determine was what, exactly, Wilson was made out of. Most volleyballs are made of synthetic leather, but Cast Away is 20 years old, so I had to be sure. Eventually I found an auction for a screen-used volleyball from Cast Away still in its packaging (from before Wilson got a face). Indeed, the side of the box said the ball was made from “Top Quality Synthetic Leather,” confirming my theory.

I also found a website detailing the chemistry of the typical volleyball, which explains the breakdown of volleyballs layer-by-layer. The outer layer is the aforementioned synthetic leather, which is primarily PVC plastic, then there’s usually a layer of cheesecloth-type cotton adhered with rubber glue, and the innermost layer is a rubber bladder made of polyisobutylene, a synthetic rubber. Final stage Wilson also had hair made from twigs coming from inside the volleyball. This is never explained in the movie, but the audience is left to assume that somewhere in the four-year gap in the film, Hanks got into one of his many fights with Wilson and somehow tore him open, but later regretted it and stuffed him with sticks, giving him a stranded-on-an-island haircut to match his own.

Sticks and plastic — which make up the vast majority of Wilson — both float, so after drifting away from Hanks, Wilson would likely have stayed afloat for a very long time. How long, exactly, is difficult to determine, but he would pretty much remain afloat until organisms like algae and barnacles weighed him down, eventually sinking him. “It would float initially and, as more barnacles and other fouling organisms grew, it would begin to sink — that is, if the materials had a specific gravity less than that of seawater. If it was made of materials heavier than seawater, it would sink quickly,” explains Captain Charles Moore, an oceanographer and boat captain who helped to bring a great deal of attention to The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a giant island of garbage more than twice the size of Texas in the middle of the North Pacific ocean.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch was originally given its name by a prominent oceanographer by the name of Curtis Ebbesmeyer, who explains to me that Wilson could have ended up in one of the two big garbage patches that fall between Australia and South America. These two patches exist in what is known as the “Heyerdahl Gyre,” the circular pattern of the ocean in the South Pacific. While we don’t know exactly where Hanks’ island was in Cast Away, we’re told that it was “600 miles south of the Cook Islands,” which are 3,000 miles east of Australia, putting Wilson firmly in the Heyerdahl Gyre.

If Wilson was caught in one of those garbage patches, he’d likely still be there 20 years later in a giant island of trash. Or he would have washed ashore on a small island somewhere in the gyre, as Ebbesmeyer explains that islands act as magnets for garbage in the ocean, washing ashore from the force of the ocean currents. Wilson may have even ended up back at the very same island that he and Hanks escaped from.

Were he to somehow avoid being absorbed into a garbage patch, Wilson might also still be floating around in the ocean. “It takes about six and a half years to float around the Heyerdahl Gyre,” Ebbesmeyer explains, so if he’s still floating and hasn’t washed ashore, Wilson would currently be on his fourth trip around the gyre.

That is, if he’s still floating — as Moore explained, eventually, Wilson would sink, though how long that would take has so many variables that it’s basically impossible to determine. “While he’s out there, Wilson would be subject to photodegradation, which means he would be broken down by exposure to the sun,” explains marine biologist Maddie Kaufman, who is the outreach director of Debris Free Oceans, an organization dedicated to cleaning garbage — like volleyballs — from our oceans.

Kaufman goes on to say that as the sun beat down on Wilson, he’d fall apart, which raises the question of what would become of his components. Again, Wilson is made up of synthetic leather, synthetic rubber and rubber glue — all of which are plastic — as well as a little bit of cotton and a bunch of twigs. The amount of cotton is negligible, and it’s also natural, so Kaufman says it would get eaten up by microorganisms without much difficulty. The twigs are also natural, but before getting eaten by organisms like shipworms — which are actually tiny clams that eat wood — they might provide shelter for fish, as Kaufman explains, “many fish use driftwood as a means of shelter, swimming under it to hide from predators.”

The rest of Wilson is just different kinds of plastic, and as he photodegrades, flakes of plastic will fall from him. Kaufman explains that those flakes are indistinguishable from food by many fish, so it might get eaten by something tiny, like an anchovy, which then gets eaten by a bluefin tuna, which then gets eaten by a shark. At every stage of the food chain, some plastic would be pooped out, and some would remain in the animal forever, this is why so much plastic is now lodged in the bodies of ocean life. Kaufman also says this might take a more direct route to the shark, as a shark might mistake Wilson for prey, eating much of him before he breaks apart. “If this happens, a shark might stop eating because their stomach would feel full. Eventually, the shark might starve to death because plastic was permanently lodged in its stomach,” Kaufman says.

And that’s pretty much it for the possible fates of the fictional Wilson — he’s either stuck in a giant ocean garbage patch, or busy poisoning entire aquatic food chains. But what about the real Wilson? Or, if you will, the actor who portrayed Wilson?

The most commonly shared story online is that former FedEx CEO Ken May bought a screen-used, late-stage Wilson at an auction, paying over $18,000 for him, so naturally I wanted to see if this was actually true. I was hoping May would tell me that Wilson is spending his retirement in a dust-proof shrine, or that maybe he was chilling with Wilson on the couch as we spoke on the phone — instead, I just get a reminder that people who write blogs should do some damn fact-checking now and again.

“I don’t know where that story came from, but about 10 or 12 years ago, people started to call me a few times a year to ask me about this ball,” May says. “Every time I give a speech or something, someone in the audience asks me about this, and a few years ago, when I was living in Dallas, a local radio station called me because Tom Hanks was in town and they wanted me to bring Wilson down for a reunion. It’s hilarious, really — I’ve been the CEO of four major companies and nobody ever remembers that, they just want to know about that dang ball.”

So since Wilson isn’t with May, I did a little more digging and found two auctions that sold screen-used Wilsons (there were 20 of them total). One of them was the auction I mentioned earlier, which sold for a mere $2,250, but that one was from before Wilson got a face, so it’s hardly the true Wilson. The other auction was a late-stage, twig-haired Wilson, which is exactly the Wilson I was looking for. This Wilson sold in 2013 for a whopping $40,000 to an unnamed buyer (and the auction site never replied to my request for their info).

As for the other 18 Wilsons from the film, well, it’s hard to say what became of them. Perhaps they’re with prop maker Robin L. Miller, who worked on Cast Away, or maybe, like so much other plastic on Earth, they ended up in the ocean, floating around in one of the gyres in a vast island of trash. Or maybe they were eaten by the marine life which so often consumes our plastic nowadays. Wherever those Wilsons are, they’re definitely not in the home of former FedEx CEO Ken May — that much, we can be sure of.